By Ejaz Haider

Prologue

Donald Trump is back, only the second American president after Grover Cleveland (1885-1889; 1893-1897) to win non-consecutive terms, and he is making a lot of people within and outside the United States nervous. Most believe that Trump is bad news all round, someone who “made divisiveness the calling card of his presidency”, as journalists Peter Baker and Susan Glasser put it in their book The Divider.

“The former president, twice impeached and twice acquitted, is the only chief executive since the founding of the nation to obstruct the peaceful transfer of power,” they wrote in their 2022 book. “The Trump era is not past; it is America’s present and maybe even its future.”

The Trump era is indeed the US’s future, at least for the next four years. But four years is a long time for someone who Republican Senator Lindsey Graham had called a “wrecking ball” in 2015 and former president George W. Bush’s son Jeb Bush described as a “chaos candidate” who will be a “chaos president.”

The US is in the moment of what went wrong, which means how and why Kamala Harris lost. As always, it is the proverbial tale of blindfolded men asked to describe the elephant by touching various parts of the animal’s anatomy. With too many variables to deal with and heuristics coming into play, it’s difficult to get the elephant right. Or maybe make it simple, as an African-American analyst on CNN did: “Well, if America wants Trump, then let America have him.”

Will Donald Trump’s second stint as US president be any different from his first stint in office? While Americans are more concerned with his domestic policies, people around the world are, understandably, wondering how his foreign policies will impact them. Ejaz Haider explores what the maverick populist’s global priorities might be and whether the world can expect any radical shifts

David Brooks, writing in the New York Times, went for a Marxian, class-clash analysis (yes, in NYT, if you can believe it!) titling the op-ed, ‘Voter to Elites: Do You See Me Now?’ As he put it: “The great sucking sound you heard was the redistribution of respect,” made by those in the “bottom decile.”

Tom McTague at UnHerd.com was more snarky, though he too seemed to be grappling like everyone else to figure it out. “Trump horrifies many outside the United States, but like Tony Soprano or Walter White [from the series The Sopranos and Breaking Bad, respectively], all the more so because they see something in him that they recognise. He is a portent. Harris is little more than her caricature on SNL [Saturday Night Live].” Gets marks for sarcasm but doesn’t tell us much about why, even if we can get to the how.

“We are back in Trump’s world and we don’t yet know what he is going to do with it,” says McTague though perhaps the more ominous bit should be about Trump becoming better at being Trump by knowing how to deal with Washington and its power elites, like “the velociraptors in the movie Jurassic Park that proved capable of learning while hunting their prey, making them infinitely more dangerous.”

And that brings us to how Trump will approach the external world. In Fear, the first of Bob Woodward’s Trump trilogy, Woodward told the reader that White House Chief of Staff John Kelly referred to Trump as an “idiot” and “unhinged”, while Secretary of Defence James Mattis thought Trump had the understanding of “a fifth or sixth grader.”

His approach to the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (Nato) and the US allies was roundly criticised, his boorish behaviour with world leaders provided much acerbic ammunition to late night shows hosts, as was his admiration for strongmen like Vladimir Putin and North Korea’s Kim Jong Un.

The beltway pundits, raised on theories of international relations and the nuances of statecraft, thought he could not be dressed in any theoretical robes, that he was transactional, an isolationist, whose approach to statecraft was antiquated and out of tune with the geopolitical realities of the 21st century. Or, as Wayne Barrett, the late investigative reporter who wrote a definitive book on Trump’s real estate dealings, said, “Everyone else in the movie that Donald Trump is making with his life…is an extra.”

The US is in the moment of what went wrong, which means how and why Kamala Harris lost. As always, it is the proverbial tale of blindfolded men asked to describe the elephant by touching various parts of the animal’s anatomy. With too many variables to deal with and heuristics coming into play, it’s difficult to get the elephant right. Or maybe make it simple, as an African-American analyst on CNN did: “Well, if America wants Trump, then let America have him.”

Narcissist he certainly is. But is Trump also inconsistent and whimsical?

Trump 2.0 and the World

In a January 2016 assessment for Politico, titled ‘Trump’s 19th Century Foreign Policy’, Thomas Wright of the Brookings Institution sought to dispel the impression that Trump’s views are confused. He argued instead that they are consistent and have a long history.

“One of the most common misconceptions about Donald Trump is that he is opportunistic and makes up his views as he goes along,” wrote Wright. “But a careful reading of some of Trump’s statements over three decades shows that he has a remarkably coherent and consistent worldview, one that is unlikely to change much if he’s elected president.”

This was about a year before Trump took oath as the 45th president on January 20, 2017. What was Trump’s overall message? That the liberal international order the US helped create and sustain gives America a raw deal and must go.

According to Wright, Trump “has three key arguments that he returns to time and again over the past 30 years.” America is overstretched; US allies have taken advantage of it; the global economy doesn’t serve America well. What’s the fix? America needs a strong leader and, as the Republican slogan goes, “Trump will fix it.”

This might be a pre-WWII or even 19th century approach to interstate relations, but it was Trump’s view as the 45th president and it will be his view as the 47th, and this time he understands Washington. He isn’t arriving there as a novice.

In an interview to Playboy magazine in 1990, Trump was asked what would a President Trump foreign policy be like. This is what he said: “He [Trump] would believe very strongly in extreme military strength. He wouldn’t trust anyone. He wouldn’t trust the Russians; he wouldn’t trust our allies; he’d have a huge military arsenal, perfect it, understand it. Part of the problem is that we’re defending some of the wealthiest countries in the world for nothing… We’re being laughed at around the world, defending Japan.” Fast forward 17 years, and that’s exactly what President Trump said and almost did.

In her 2011 book, Leaders at War, Elizabeth N Saunders, professor of political science at Columbia University, argued that leaders’ beliefs determine how they operate. Although the book is about how “beliefs shape intervention choices”, the argument can be said to hold true for much else the leaders do internally and externally, because “these beliefs influence” their decisions.

Beyond this, of course, are many other complexities and competing factors that weigh in on how decisions are ultimately made. But a predisposition evolved over many years is an important factor in how people and, in this case, a president will behave.

Trump’s domestic agenda is outside the scope of this article. Nonetheless, it should be obvious that certain, if not all, of his actions at home — the treatment of immigrants or racial and religious minority groups — could impact some of his foreign policy approaches.

For instance, a Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) exit poll indicates that Jill Stein got 53 percent of the Arab/Muslim vote, while Harris and Trump secured 20 and 21 percent respectively. One could argue, as many analysts have, that Harris lost a big chunk of the traditional Arab/Muslim vote because of Biden’s “ironclad” support for Israel’s genocidal war in Gaza. This is unlikely to impact Trump for two reasons: one, he is beginning his term and has no election pressures; two, affected minority groups, unless a third political force can emerge in the United States, will be forced to vote one way or another — or just sit it out.

Similarly, if Trump were to act on the recommendations contained in the Heritage Foundation’s nearly 1000-page report titled ‘2025 Agenda’, he could end up reconfiguring the institutions of the US federal government in some radical ways. That could have a profound effect on how the government works, or cannot, and whether the concept of checks and balances can be maintained in the system.

While at the time of writing this the appointments hadn’t been finalised, it seems that, for cabinet appointments dealing with domestic affairs, Trump is “building a governing team in his own hardline MAGA image,” as reported by CNN, leading to “the modern age’s most right-wing West Wing [which] will target Washington elites and undocumented migrants [and] seek to shred the regulatory state.”

On the foreign policy and security side, however, “the president-elect’s national security picks so far suggest a more mainstream Republican approach to foreign policy.”

But it’s time to get to some specifics. I intend to flag three areas: Nato and European security in the backdrop of the Russo-Ukraine war, peer competition with China, and the Middle East wars.

NATO, EU and the Russo-Ukraine War

Back in April 2016, when Trump was looking to win primaries to get the Republican nomination as the party’s presidential candidate, he told a small rally in Milwaukee that he would be fine if Nato broke up.

He said, “That means we are protecting them [Nato allies], giving them military protection and other things, and they’re ripping off the United States. And you know what we do? Nothing. Either they have to pay up for past deficiencies or they have to get out. And if it breaks up Nato, it breaks up Nato.”

As the 45th president, Trump did not go to the extent of breaking up Nato, but he definitely did two things: he told the European allies that they have to do more to bear the expenses of the alliance, and he instilled a lasting fear that he might just walk out.

Europe’s defence spending has, of course, gone up over the last decade, as a recent International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) report indicates. The report, launched at the Prague Defence Summit held on November 8-10, says spending began to go up after Russia’s annexation of Crimea and has further picked up after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In between, 2017-21 were the Trump years, when he pushed Nato ‘s European members to spend more on defence, up to and beyond two percent of their GDP, and to be less reliant on US military cover.

But the IISS report also identifies investment problems and production capacities that raise a question mark over the sustainability of this trend. The Europeans have focused on systems needed by Ukraine and, in many cases, have provided support to Kyiv from their own inventories. That has, paradoxically, again forced them to rely on US support and military cover, despite enhanced defence spending.

Europe’s problem is best illustrated by Germany, where Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s coalition went under the same day Trump won the election. In 2022, three days after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Scholz spoke at the Bundestag to deliver his “Zeitenwende” speech: “Februar 2022 markiert eine Zeitenwende in der Geschichte unseres Kontinents [February 2022 marks a watershed (or turning point) in the history of our continent].” The speech spawned hundreds of analyses.

Germany was to allocate a €100 billion one-off sum for its armed forces and the money was to be used “for necessary investments and armament projects.” Close of three years from that speech, Scholz’s finance minister, Christian Lindner, has been fired and a report by the German Council on Foreign Relations’ Action Group Zeitenwende says the policy has failed and “Germany now needs a comprehensive strategic reset — and bold leadership in domestic as well as foreign policy — to arrest its decline and ensure its security, prosperity and democracy.”

Germany is just one example. The idea of “Europe” as a collective noun is unravelling along several fault-lines: domestic politics of member states, the approach to the Russo-Ukraine war, dealings with China and, to a lesser but not insignificant extent, the Israel-Palestine issue.

Trump, already predisposed to pulling the US back from its imperial overstretch, will be encountering a Europe where much has changed since he was last in the Oval Office. His approach to Nato and the Russo-Ukraine war would be two important factors that, in combination with the domestic politics of European states and rising economic problems, could determine the EU’s and Nato’s future, the shape of Europe and cross-Atlantic relations. Would Trump withdraw from Nato? Maybe not. Could he let it fade away? Possible. One thing is sure: he doesn’t like Nato and that’s more than just the problem of paying for Europe’s defence.

In 2020, at the World Economic Forum, Trump told European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, “By the way, Nato is dead, and we will leave, we will quit Nato.”

On December 14, 2023, the US Congress approved a bipartisan bill that bars any president from unilaterally withdrawing from Nato, a measure aimed at establishing “Congress’s commitment to the Nato alliance that was a target of former President Trump’s ire during his term in office.” The bill stipulates that any withdrawal from Nato requires an Act of Congress.

But it’s the US president that determines whether or not to commit American military power in any conflict. That’s not Congress’ remit. Article 5 of the Nato Treaty, while establishing the concept of collective defence, maintains that every member state can take such “action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force…” That gives Trump much space to decide what action to take. Also, whatever action is to be taken becomes binding only after all member states agree to it and invoke the Article 5 commitment. In the end, none of the legal-treaty provisions really matter. As Ivo Daalder, a former US ambassador to Nato, has noted in a piece for Politico, “What makes a security alliance effective isn’t some legal diktat… it’s the trust that allies have in each other, that they will come to each other’s defence, and the credibility of that commitment in the eyes of their adversaries.” In that important respect, Europe doesn’t trust Trump, and for good reasons.

But what about the Russo-Ukraine war, a post-Trump’s first presidency crisis? Shouldn’t he be worried? Doesn’t that make Nato unity ever more important? Not necessarily. Trump has already said he could get it resolved in “24 hours.”

“It is not possible to end the Russia-Ukraine war overnight,” Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov said at a press conference on November 6, in reference to Trump’s statements. But Peskov also said that Russia has “repeatedly said that the United States can help end the conflict in Ukraine.” Meanwhile, at the Valdai Discussion Club in Sochi, Russian President Vladimir Putin congratulated and praised Trump and said “Moscow was ready for dialogue with the Republican president-elect.”

This is smart play by Putin. He knows Trump doesn’t like wars (it’s quite another thing that his Israel-Middle East policy is largely responsible for the current crisis in the region, a point discussed later). Putin also believes Trump is more concerned about stymieing China’s growth than he is in kneecapping Russia.

While Trump hasn’t given a blueprint on how he would end the Russo- Ukraine war in “24 hours”, his Vice-President-designate, JD Vance, who is even more openly opposed to US support for Ukraine, has indicated scaling back US weapons supply to Kyiv, getting the two sides to freeze the territorial status quo, create a demilitarised zone roughly along the Dnipro River and getting a multinational European force to man that DMZ. Most tellingly, Ukraine’s Nato bid will be struck down.

Whether Ukraine accepts this formula is anybody’s guess. What is clear and known is the fact that, without active US military and financial support, Kyiv cannot sustain the war. The Trump White House is likely banking on a rational calculus by Kyiv that, without US support, Ukraine cannot manage Russia and might lose more territory if the current status quo is not frozen through a deal.

Competition with China

This one’s easier in some ways because not much is going to change on China. Trump started an unprecedented trade war against China in July 2018 and imposed tariffs that went as high as 25 percent on Chinese imports coming into the US. On the campaign trail this time, he suggested the tariffs could go as high as 60 percent, even more.

But the US-China peer competition is more than about Trump’s gut and tariffs. It is a structural issue, what political scientist John Mearsheimer described as the “tragedy of great power politics.”

When Biden got elected, China thought that he might approach the issue differently and reverse some of Trump’s actions. That did not happen. Biden continued with Trump’s policies, adding a further dimension to it: taking measures to deprive China’s tech industry of cutting-edge semiconductors.

The Biden administration called it the “small yard, high fence” strategy. China, as an emerging power, challenges the US, the existing hegemon.

The structural bind being the driving force, Trump will not change course on China. If anything, he would double down on the policy he began and Biden continued. As he said at the Economic Club of Chicago, “To me, the most beautiful word in the dictionary is tariff. It’s my favourite word. It needs a public relations firm.”

The argument by mainstream economists that tariffs actually amount to a tax on American consumers and make the economy less efficient doesn’t impress Trump. He believes that “tariffs are misunderstood as an economic tool.”

It’s not possible to go into the details of how Trump will approach the Australia-India-Japan-US Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) and Aukus [Australia, UK and US security partnership] arrangements, but doubts have already surfaced about whether Australia will have full control of the Virginia class submarines or even, as former Australian prime minister Malcolm Turnbull said in July this year at the Australia Institute, Australia will get those submarines, given that the US Navy is short of its own requirements and the Aukus legislation says Australia will get these submarines only if the “US president can certify that their Navy doesn’t need these submarines.”

There’s tension here between Trump’s approach to China and his “America first” approach. So far, he has reconciled it by hobbling China’s economy through sanctions and tariffs. It will be interesting to see if he would also go for cordoning China through Quad and/or Aukus and take a more aggressive, militaristic approach.

The Greater Middle East

Trump has often said he doesn’t like wars. Presenting the comprehensive review of his administration’s Afghanistan strategy on August 21, 2017, he said, “My original instinct was to pull out — and, historically, I like following my instincts.” He went along with his generals at the time, nonetheless. Later, he would call his generals “idiots.”

But in the Middle East, Trump followed a policy that, in many ways, led to the October 7 Hamas attack, even as he thought he was executing a comprehensive peace strategy by pushing for and facilitating deals such as the Abraham Accords, which pushed normalisation of bilateral relations between Israel and the UAE, Bahrain, Sudan and Morocco. Here’s what he did wrong.

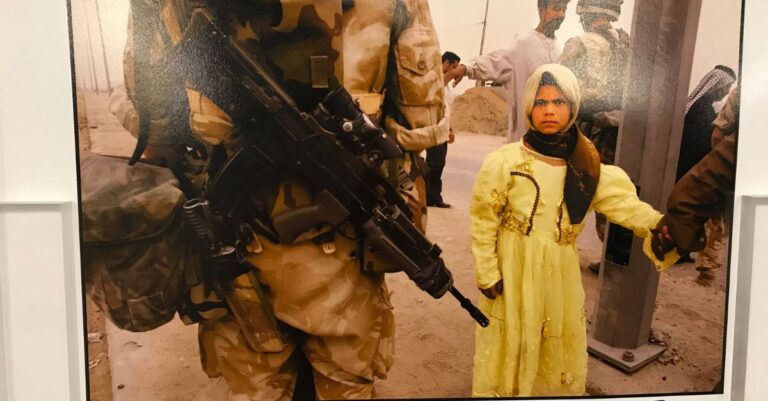

Trump assumed that by getting the Arab states to normalise with Israel, he would reduce the chances of any conflict, even as conflicts raged in Syria and Libya, Egypt remained an oppressive military dictatorship, Iraq continued to suffer instability and Iran was pushed to the wall by the US when Trump walked out of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action and slapped a new set of sanctions on Tehran. But most importantly, he wittingly prescinded the Palestinians from his supposed grand peace initiative, allowing Israel to carry on with its slow, structured violence against them.

With his hand placed on a glowing orb, what one analyst called a “mysterious spheroid”, and standing with the Saudi King and Egypt’s Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, Trump thought the Middle East could be steered without having any viable policy regarding internal wars and by burying the Palestinian cause. That was not to be.

Trump recognised Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and moved the US embassy there, essentially upending America’s decades-old policy and inflaming passions. He closed down the Palestinian Liberation Organisation’s office in Washington and allowed Israel to annex the Golan Heights. With his son-in- law and adviser, Jared Kushner, running point on his policy, Israel went on a spending spree to build more settlements.

Trump’s former US ambassador to Israel and a certified Zionist, David Friedman, was fully on board and consorting with the likes of far-right Israeli politician Itamar Ben-Gvir, Israel’s Minister for National Security since 2022. Friedman’s daughter ‘made aliyah’ (moved to Israel) during this period. Result: “Operation Al-Aqsa Flood”, as Hamas called the October 7, 2023 attacks.

The settler-minister Ben-Gvir has already welcomed Trump’s election victory, saying that “this is the time for sovereignty, this is the time for complete victory.” As Trump 2.0 starts next year, he will have two choices: he could either go back to what he started in 2017 and give the Israeli right the “complete victory” it is looking for or, as he told the Muslim leaders, “stop Netanyahu’s war” and start a genuine political process whose centrepiece is the Palestinian question.

Going by his previous approach, it seems that he will allow Israel a free hand to resettle Gaza by exterminating more civilians and going on a settlement spree in Occupied Palestinian Territories, including encroaching on the Palestinian Authority’s already dwindling control of Area A. The policy would likely be pegged on the assumption that Israel has already decimated Hamas and degraded Hezbollah and it will take many years for the groups to regain the capacity to attack Israel. In the meantime, they might resort to small attacks but Israel has the capacity to deal with that.

The presumed “success” of this policy would require a complete surrender by the Arab states, which Trump — like previously — would aim to secure through lucrative defence and commercial deals. How this policy might unfold is of course unknown and in the future, but some trend lines are visible.

Corollary: the Middle East will remain unstable and poised for further flare- ups. A lot will also depend on how Trump approaches Iran. If he goes along with an Israel attack and further weakens Iran, the region will become even more unstable.

Epilogue

Our broad picture so far has been that, ideally, Trump would like to pull America back from its global overstretch. He doesn’t like global trade and multilateral trade arrangements. For instance, he pulled out of the Trans- Pacific Partnership (TPP), which included 11 other Pacific Rim countries, including Japan. Most trade experts in the US believe America is still paying for it.

According to a Cato Institute assessment citing a study by the US International Trade Commission, the arrangement would have resulted in “a real US GDP increase of $42.7 billion through 2032 as a result of TPP membership, while a Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) working paper foresaw gains to US real incomes of $131 billion through 2030.”

Trump did the same with the North Atlantic Free Trade Agreement or Nafta, calling it the “worst trade deal ever made.” Nafta, signed in 1994 between the US, Canada and Mexico, had “contributed to an explosion of trade between the three countries and the integration of their economies, but was criticised in the United States for contributing to job losses and outsourcing.” Trump forced the other two countries to renegotiate the deal as the United States- Mexico-Canada Trade Agreement.

Some would call it quintessential Trump strategy. Bull in, talk tough and get a deal which is presumably (or should one say ‘Trumpuably’) better for America. Put another way, “Though this be madness, yet there is method in it.” The idea is less about pulling out of multilateral arrangements and more about forcing other states to fall in line.

Another lesser-known example is the Korea-US Free Trade Agreement or Korus. Journalist Bob Woodward opens his book, Fear, by telling us that, “For months, Trump had threatened to withdraw from the agreement, one of the foundations of an economic relationship, a military alliance and, most important, top secret intelligence operations and capabilities.”

He had even written a one-page draft letter to the president of South Korea. Gary Cohen, his top economic adviser, was “appalled” and decided to

remove “the letter draft from the Resolute Desk”, and place “it in a blue folder marked ‘KEEP’.” Trump said he had told the South Koreans, “We’ll either terminate or negotiate. We may terminate.”

And this brings us to Trump’s apparent belief in the Madman Theory, outlined by economists Daniel Ellsberg and Thomas Schelling, though he has perhaps never heard of it formulated thus. In a 2023 paper for Security Studies, titled ‘Madman or Mad Genius? The International Benefits and Domestic Costs of the Madman Strategy’, political scientist Joshua Schwartz writes that Trump has “seemingly incorporated elements of the Madman Theory into his broader negotiation philosophy.”

Schwartz presents two examples: In a discussion with top cabinet officials regarding the US-South Korea trade deal, Trump reportedly told then US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer, “You’ve got 30 days, and if you don’t get concessions then I’m pulling out.”

“Ok, well I’ll tell the Koreans they’ve got 30 days,” Lighthizer replied. “No, no, no,” Trump interjected. “That’s not how you negotiate. You don’t tell them they’ve got 30 days. You tell them, this guy’s so crazy he could pull out any minute… You tell them, if they don’t give the concessions now, this crazy guy will pull out of the deal.”

He managed to force South Korea through a number of measures, including sweeping tariffs on steel imports and getting Seoul to open its market for US pharmaceuticals. The details don’t matter. What matters is Trump’s style of negotiating from a position of presumed or real strength.

The strategy didn’t work with North Korea. Trump began by threatening to “totally destroy” North Korea and bring on Pyongyang “fire and fury like the world has never seen.” Kim Jong Un didn’t blink and Trump changed tack by reaching out to Kim. The “problem” hasn’t gone away because it is structural and can’t vanish by a friendly meeting at the Korean Demilitarised Zone. Schwartz’s paper argues that the Madman Theory doesn’t work. He traces it back to Richard Nixon, who told his Chief of Staff Bob Haldeman: “I want the North Vietnamese to believe that I’ve reached the point that I might do anything to stop the war. We’ll just slip the word to them that, ‘For God’s sake, you know Nixon is obsessed about Communism. We can’t restrain him when he is angry — and he has his hand on the nuclear button’ — and Ho Chi Minh himself will be in Paris in two days, begging for peace.”

Trump did the same with his Nato allies. With Russia, he could begin with the same approach, or start by telling Russia to negotiate and then put pressure on the Kremlin.

But his most complicated challenge will be the Middle East. Last time, he walked out of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) or the Iran nuclear deal. That move has actually pushed Iran closer to the bomb. If he ratchets up the pressure or, worse, goes along with Israel’s Iran policy, he will be pushing the Greater Middle East into a big flare-up.

The writer is a journalist interested in security and foreign policies. X: @ejazhaider

Published in the Dawn