By Mukul Kesavan

The bhoomi pujan in Ayodhya with the prime minister of India presiding was an important moment in the political evolution of the Republic. Narendra Modi had a double role. He was both jajman and karta: the Hindu client who had commissioned the ceremony on behalf of the Hindu Undivided Family, now known as India, of which he was the regnant patriarch.

The most stringent critic of nationalism will concede that nations frame our lives. A sense of national belonging shapes our leisure (watching Test cricket), our collective sense of the past (Gandhi and Ambedkar as fictive ancestors), our literary output (Ghare Baire and The Shadow Lines) and our mental maps of the world. We have learnt from historians of nationalism such as Benedict Anderson and Eric Hobsbawm that nations aren’t given, they are imagined. The ritual at Ayodhya, carried live by every television news channel in India, marked the enthronement of the idea of India as a Hindu Nation, governed by an ideologically Hindu prime minister, on behalf of its mainly Hindu People.

The construction of the Ram Mandir where the sangh parivar wants it built won’t lead to apocalypse. The world will look the same the morning after, but the common sense of the Republic will have shifted. It will begin to seem reasonable to us and our children that those counted in the majority have a right to have their sensibilities respected, to have their beliefs deferred to by others. Invisibly we shall have become some other country.

I wrote the previous paragraph twenty years ago as the conclusion of a short book called Secular Common Sense. To quote yourself is a gruesome thing to do; my excuse is that now that the ground has been consecrated, judicially and ritually, those of us who opposed the violent campaign for a temple in Ayodhya must reckon with the reality of the new country that it has ushered into being.

The gravitational pull of the new political reality that the temple symbolizes is apparent. Kamal Nath and Priyanka Vadra, leaders of India’s principal Opposition party, the Indian National Congress, have publicly signaled their support for the Ram Mandir. A mandir for Ram Lalla used to be the sangh parivar’s pet project; now it’s every neta’s baby.

It isn’t just professional politicians who have been converted to the temple’s cause. Pavan Varma, writer, diplomat and erstwhile spokesperson of the Janata Dal (United), has written recently of his exasperation with the carping of liberals about building the Ram temple at Ayodhya after the dispute had been definitively resolved by the Supreme Court. Another progressive notable likes to tell of the time a plain-spoken citizen from Haryana set him right on the Ram Mandir when he asked, rhetorically, that if a Ram temple wasn’t to be built in Ayodhya, where was it to be built, in London?

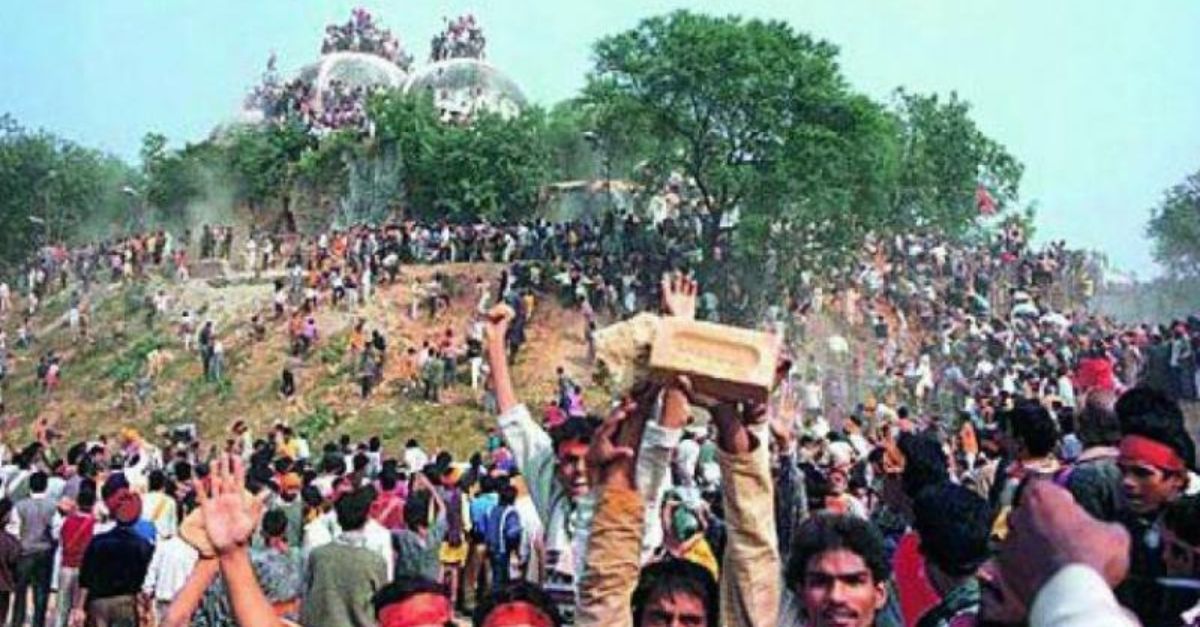

This simple question from this sturdy citizen is intended as a reproach to deracinated progressives cut off from the strength of popular feeling. The history of administrative deceit, political complicity and organized violence that led to the razing of the Babri Masjid and then roiled its aftermath is erased and replaced by an alternative narrative: the long-suffering Hindu majority’s spontaneous, reasonable and just demand for a temple to its god in Ayodhya, his birthplace.

This is a sleight of hand that progressives should refuse. The movement to raze the Babri Masjid wasn’t a stand-alone project. It was one trunk in a grove of bigotry, inseparable from the other branches and roots of that toxic tree. The political project that trivialized pogrom, normalized lynching, criminalized dissent, physically attacked universities, and introduced a religious test for citizenship also gave us the Ayodhya movement. To make out that the building of the Ram temple is a necessary concession to a deep well of religious feeling is disingenuous. Once the bhavya mandir is built, it will be less a religious shrine than a symbol of the Hindu ownership of the Indian nation.

The more sophisticated case for embracing the mandir and moving on is made up of two related arguments. The first one is simple: political defeat in a democratic republic has consequences and liberals shouldn’t be sore losers. This is bad advice: no political project worth the name should be abandoned after a couple of electoral routs. Had the sangh parivar taken this advice to heart after the drafting of a liberal and secular Constitution and the subsequent decades of Congress dominance, there would be no Ram Mandir in the offing.

The related argument takes its cue from Ernest Renan’s proposition that all nations are based on selective amnesia. In his influential lecture, “What is a Nation?”, Renan argued that the political unification of France involved so much war and bloodshed that the French needed to forget their past to forge a national present. Transposing Renan to contemporary India, the move-on and live-to-fight-another-day realists argue that instead of picking at the Ayodhya scab, progressives should let it be. This would help national healing and create a less communally charged political arena in which to practise progressive politics. By drawing a line under the razing of the mosque, via a kind of willed forgetfulness, liberals would sidestep the communal argument that in a Hindu-majority India, only one party can win.

It’s not unreasonable to argue that in a hundred years the Ayodhya confrontation might be reduced to a footnote in some unread political history of the early 21st century. This sounds plausible because we know that it is hard for us to be proportionate about the present, to see it in perspective. But the question to ask ourselves is this: will the razing of the Babri Masjid and the building of the Ram Mandir be forgotten because these events became politically irrelevant, or will they be taken for granted because they were foundational to everything that followed? If the Axis powers had won World War Two, Kristallnacht would be footnoted in today’s textbooks as a passage of cathartic violence that reinvigorated Aryan nationalism.

It is inevitable that some politicians and intellectuals will tack right towards India’s shifting centre. They aren’t necessarily acting in bad faith. The holding actions and compromises that parties and individuals resort to as they fight for their lives against the sangh parivar’s juggernaut need understanding, not denunciation.

But to accept the ideological premises of the sangh parivar is the opposite of living to fight another day. If a willed amnesia about the vandalism and violence of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement is the necessary preliminary to practical politics, the battle is lost already. The razing of the Babri Masjid and the raising of the Ram Temple are two sides of the same coin. That coin is the currency of Hindu nationalism. Liberals, socialists, progressives and decent constitutionalists of any stripe can’t deal in it.

Milan Kundera is a better guide to political action in the present moment than Renan. The business of progressive politics in this precarious time is to remember, not forget, the instrumental and ideological violence of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement. “The struggle of man against power,” writes Kundera, “is the struggle of memory against forgetting.”

(This article first appeared in The Telegraph)