When Stone Walls Cry: The Nehrus in the Prison

Mushirul Hasan ( 2016)

Oxford University Press

pp. x+201

Hardbound

Rs. 695/-

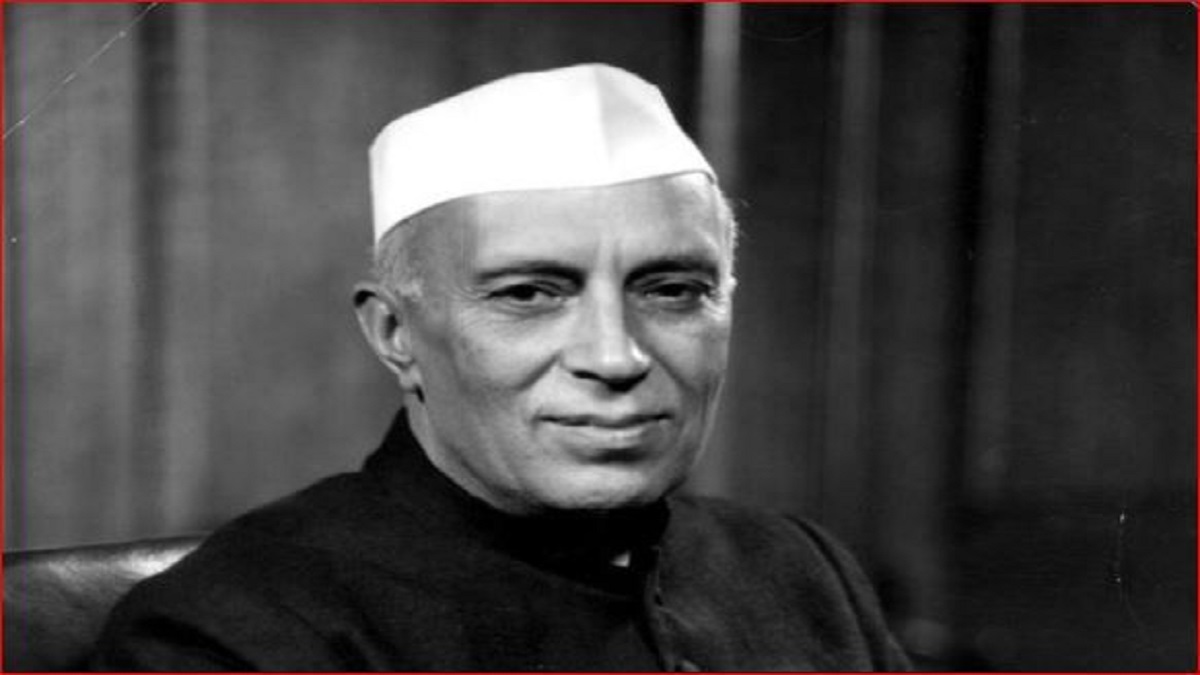

The last decade has witnessed burgeoning of different electronic materials being made on and around Indias first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. A lot of textual and video material is misinformation and slanderous while only a few of them talk about the man and his life factually.

In these strange times, even universities and the students are being targeted. Reading provides a refuge, or as some may call it, an escape from the everyday theaters of eccentricities and violence. It was a respite to pick up The Nehrus in Prison (2016) by Mushirul Hasan, a distinguished historian of colonial north India. This book is a testimony of his skill in history writing.

The book revolves around two passionate and intrepid crusaders for freedom, who adjusted well to dreary prison life. One is the proud and truculent Motilal Nehru. The other is the robust and energetic Jawaharlal Nehru. The book talks about how Motilal Nehru changed from being a moderate to radical which owed to, among other reasons, Jallianwala Bagh massacre. It deals with Nehrus, families and their extended families and friends. It talks about the region, United Provinces and the Allahabad city, where both actors were mainly based. The book deals in good detail about the womenfolk and friends. Two full chapters are devoted to the same. We get to know various aspects of the freedom struggle right from the early 20th century till Independence.

Indeed, Hasan takes us through the post-Independence period, discussing Jawaharlal Nehru’s full tenure and devoting some pages to Indira Gandhis accession to power. The focus of the book is on the prison life of all the actors in the book. I found in this book a healthy combination of history and biography.

The book also deals with a number of characters who were not in the Nehru family, yet contributed significantly to the freedom struggle. One of them was Manabendra Nath Roy, a commanding figure in the communist movement. Popularly known as M.N. Roy, he wrote about 3750 pages in prison. These were written between 1931 and 1936 in Kanpur, Bareilly, Almora and Dehradun prisons, all in what is today Uttar Pradesh. He wrote on both philosophical issues and facets of the nationalist movement.

Similar was the case with Kailash Nath Katju, who had argued the Meerut Conspiracy Case in 1933 in the Allahabad High Court. He wrote his autobiographical account The Days I Remember in the Naini Central Prison in the winter of 1942-3, when he was detained for taking part in the Quit India Movement.

In the 1920s, Mohammad Ali Jauhar (1878-1931) and Hasrat Mohani (1875-1951) wrote ghazals in jail. Progressive writers such as Josh Malihabadi (1894-1982), Faiz Ahmad Faiz (1911-1984), and Ali Sardar Jafri (1913-2000) were put in prison and matured as poets there. This proceeds naturally because of their conviction that independence, democracy, socialism, secularism, and faith in progress were requisites for the production of great literature. They used the symbolism of qaidi (prisoner), qaidkhana (prison), and daar-o-rasan (gallows) to lead mankind towards emancipation. Faiz wrote Zindanama (Prison Writings) to describe what the experience of imprisonment did for his development as a poet.

There were two personalities who influenced the Nehrus very deeply, i.e., M.K. Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore. Both the Nehrus, despite disagreements with Tagore and Gandhi, were their great admirers. Tagore had a sense of universal humanity and sought to identify areas of East-West cooperation. But it was in Gandhi that Jawaharlal Nehru found his happiest moments. There is a long list of friends imprisoned; the names of Maulana Azad, Hakim Ansari and Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan deserve special mention. A full chapter is devoted to the work done by the Nehru women be it Swarup Rani, Kamala Nehru or Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit.

As the spirit of nationalism grew, Hindu communalism also increased against it. An instance from the book illustrates the point. In 1910, Sarla Chaudhurani, granddaughter of Debendranath Tagore, wanted a few mantras from the Veda to be sung at the Congress session in 1910. But Malaviya interdicted the song on the ground that the Shastras prohibited their singing in the presence of non-Hindus. Further, as the head of the All India Independent Party, Madan Mohan Malaviya used communal tactics to discredit his Swaraj Party rivals in the 1925 municipal elections, and in the 1926 provincial legislative councils elections. In the Central Provinces, the All India Independent Party was led by Malaviya and Lajpat Rai, and the election battle ran clearly on communal lines. Elections were won by polarising Hindus, a political strategy prevalent till date.

It would have been helpful if Hasan had stated how Hindutva ideologues responded to the issue of separate electorates to the Dalits as demanded by B.R. Ambedkar. However, Hasan concedes that Jawaharlal Nehru failed to understand Jinnahs point of view on the issue of safeguards for minorities. Hasan has missed mentioning the Sapru Committee report (1945).

Notwithstanding these limitations, I found in the book a ringing romance of the historians admiration for the Nehruvian vision of India. Mushirul Hasan posits that the Nehrus had universalistic and humanistic viewpoint in different spheres of lifereligion, culture, nationalism, science, women empowerment or development. This explains why the prison could not crush the spirits of Nehrus and they held their heads high. This book is a living testimony to the ideals for which they stood rock hard.