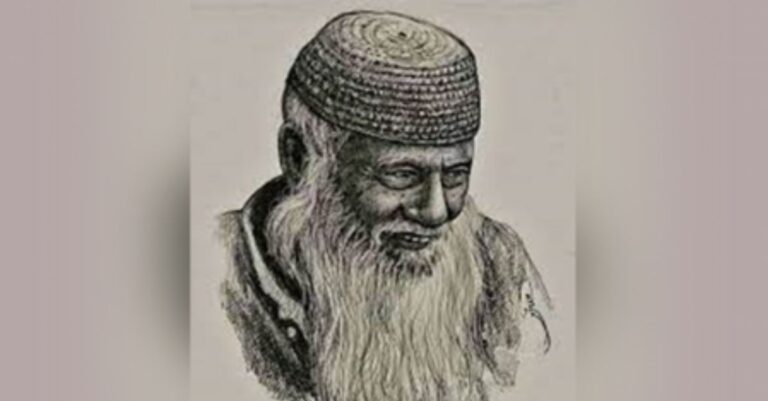

Born on 27th December 1797, Mirza Asadullah Khan ‘Ghalib’ is considered as the greatest Urdu poet of the 19th century. A peek into his life, poems and thoughts sheds light on the ethos of the 19th century Delhi and the conception of Muslim identity during those times. He neither composed his poetry for a Muslim audience nor an exclusive Urdu-speaking readership. These distinctions did not matter to him. He did not subordinate himself to any form of religious authority. Belief in monotheism or tauhid and love for the Prophet and his family (ahl-i bait) alone, he considered sufficient for salvation. He emerges as a man who treated religion with a quizzical irreverence, exposing the morals of the mulla and his theology as quirky.

Pluralism personified:

Values including respect for cultural diversity, play a central role in Ghalib’s cosmopolitan outlook. Ghalib wore no sectarian badge, no sectarian colour. “I hold all mankind to be my kin and look upon all men—Muslim, Hindu, Christian—as my brothers, no matter what others may think”. Ghalib respected Hinduism, and commended Hindu sites to his readers. In October 1827, he set out for Calcutta. Part of the way he journeyed by river, and the final stage from Banaras to Calcutta on horseback. Banaras enchanted him; hence the lyrical Persian poem Chiragh-i Dair (The Lamp of the Temple) of 108 couplets. Ghalib wants the country’s special customs to be preserved. Kashi symbolizes a sign of God, and a microcosm of Indian life, customs, and beliefs. It is, indeed, the Kaaba of India: ‘If Ganga hadn’t rubbed its forehead at the feet of Banaras, it wouldn’t be pure.’

Trauma of 1857:

Ghalib weathered the storm of 1857 to record what he heard and saw in Dastanbu and letters. He stayed in Delhi for the entire period between the coming of the mutineers from Meerut in May and the successful British assault upon Delhi in September. He did not stir out of his house, though the tumult of arrests and killings reached his lane. Secluding himself in a quiet life, he turned to writing letters that became an inseparable companion, a safety valve for repressed irritation. He needed, as ever, to talk to relatives and friends, and the letters were a means of fulfilling this need. He knew that British soldiers had already ransacked Lal Qila and carried away the valuables. He knew that in September 1857 the British seized Jama Masjid. Many of the nobility’s mansions were destroyed by the British.

For a man so deeply in love with the city and its people, the death of thousands, after perfunctory trials or none at all, struck a painful blow. He bemoaned: “… and the city I live in is still called Delhi and this mohalla is still named Ballimaran mohalla– yet not one of the friends of that former birth is to be found. By God, you may search for a Muslim in this city and not find one– rich, poor, and artisans alike are gone.” In some letters, Ghalib wrote bitterly of the execution of the men of repute and noble character. His own brother, Mirza Yusuf, died in October 1857, and was buried with great difficulty. The brother’s house was plundered. Ghalib was himself arrested and brought before a colonel who let him off.

Love of Dilli:

Ghalib loved Delhi and regarded himself as a living part of Shahjahanabad. In its culture there was an increasing belief that a well-lived life was a work of art. It is therefore not surprising that he, for most of his life, lived quietly and contentedly in and around Gali Qasim Jan and Habash Khan ke Phaatak (Gate of Habash Khan). Before his death on 5 February 1869, in the house behind a mosque where he moved in early 1866, he had composed the following verse in a self-deprecatory tone: “I have constructed a house in the shadow of a mosque. This disgraceful creature has become Allah’s neighbour.”

Importance of dissent:

Though some ridiculed Ghalib at times for their own personal reasons, the theologians neither excommunicated him nor did they solemnly commit his writings to the flames. There was something of the Urdu adab in its extraordinarily tolerant attitude to Ghalib and several other poets of his time.

Quirky Ghalib:

In 1842, James Thomason, the government of India’s secretary, interviewed candidates for a teaching position at Delhi College. Ghalib, who was summoned for an interview, arrived in his palanquin. Ghalib stood outside waiting for him to extend the customary reception. After a while, the secretary came out to explain that he would accord to Ghalib a welcome befitting of his status if he had come to the governor’s durbar. The poet replied, ‘I contemplated taking a government appointment in the expectation that this would bring me greater honours, not a reduction in those I already receive.’ Thomason said, ‘I am bound by regulations.’ ‘Then I hope you’ll excuse me,’ Ghalib quipped, and came away.

Ghalib- Sayyid Ahmad Dialogue:

Ghalib was put off to find people stuck in the past, oblivious to the present, and wanted them to benefit from Europe’s science that was made accessible in translations. One example of this is his chilly reception to Sayyid Ahmad’s editing of Ain-i Akbari by Abul Fazl (1551–1602), and his description of it as a futile endeavour to extol the past which ignored the scientific accomplishments of the British. However this did not lead to any personal distance between the two. Thanks to Sayyid Ahmad Khan’s intercession, Ghalib’s pension was restored in May 1860. His philosophy was always to accept and understand change and work towards a new balance.

Conclusion:

Mirza Ghalib died with the satisfaction that his ‘poetry will win the world acclaim when I’m gone’. Truly, his words came true. Gulzar’s series of Ghalib is a good audio-visual reference to his biographical sketch. Jagjit Singh’s voice has made his ghazals reach far and wide. I hope Ghalib’s cosmopolitanism also reaches everyone’s heart in today’s time.

- This short essay is based on Mushirul Hasan’s book A Moral Reckoning: Muslim Intellectuals in Nineteenth-century Delhi (2005, OUP).