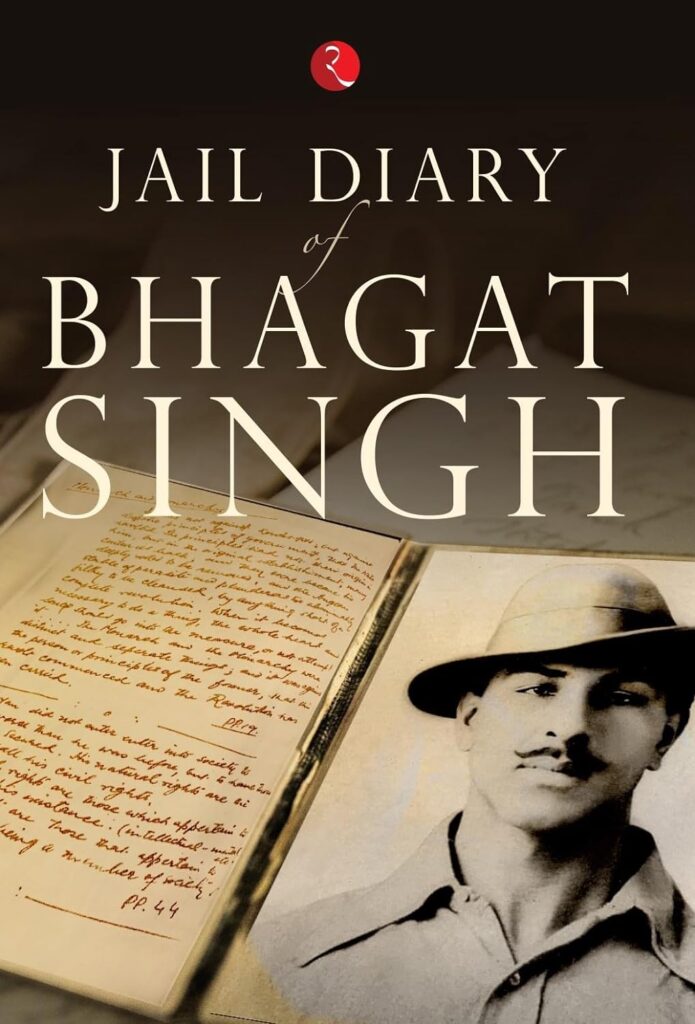

Jail Diary of Bhagat Singh

Rupa Publications

2021

200 pages

Rs 149/-

“They may kill me, but they cannot kill my ideas.”

“Tujhe zibaah karne ki khushi, mujhe marne kaa shauk,

Meri bhi marzi wahi hai, jo mere sayyad ki hai.”

Bhagat Singh (1907-1931) wrote to a great extent in the period between September 1929 and March 1931 before he was sent to the gallows a day ahead of his actual hanging date. He kept a diary that was full of “notes of daily usage, his own thoughts on freedom, poverty and class struggle and thoughts on varied political thinkers and intellectuals such as Lenin, Marx, Ummar Khayyam, Morozov, Rabindranath Tagore, Trotsky, Bertrand Russell, Dostoevsky, Wordsworth, Ghalib and many others.”

The actual page count of his Jail Diary is 404 pages, but many pages were left blank. These blank pages convey “a surreal message. Perhaps, he didn’t want to write that particular day and wanted this to be communicated.”

This book has 288 entries. The blank pages are not included. (For example, we get Entry 1, and the next Entry is 5. Entry 2, 3 and 4 are not included).

It records the many quotes from many thinkers across the continents he read during prison. The subjects are varied–from the origin of the family and the state to the desire for freedom and liberty, from the frame of mind of a revolutionary to the growth of opportunism and betrayal, from social solidarity to the rise of dictatorship and monarchy, from man and machine to the punishments of capitalism and imperialism, from bourgeois democracy to the aim of communists, from jurisprudence and justice to the science of the state and the sovereignty of the people, from religion and socialism to the wrongs of untouchability, inequality and child labour, from monarchy, anarchy, insurrection to the right of revolution, etc.

Entry 61 is on dictatorship, sub-headed into Revolutionary dictatorship and Bourgeois democracy that he considers “a great historical advance in comparison with feudalism, nevertheless, remains, and cannot but remain, a very limited, a very hypocritical, institution, a paradise for the rich and a trap and a delusion for the exploited and for the poor.”

Entry 69 is on the aim of the Communists from The Communist Manifesto: “The Communists disdain to conceal their views and aims. They openly declare that their ends can be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions. Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communist revolution. The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains.”

Entries 105 to 115 are on kinds of laws, justice and punishment. Entries 165 to 167 are on the science of the state that notes: “Ancient Polity–Rome and Sparta–Aristotle and Plato: Subordination of the individual to the State was the dominant feature of these ancient polities…In Hellas or in Rome, the citizen had but a few personal rights…and his religion was imposed by State authority. The only true citizens and members of the sovereign body being an aristocratic caste of freedom, whose manual work is performed by slaves possessing no civil rights.”

His Entry 170 enlists a host of thinkers such as Machiavelli, who “thought the Republican form of Government to be the best one” and Huguenot, Buchanan who held that the king and people are bound to each other by a pact or contract and that its violation by the former warrants the end of his rights to rule.

Entry 177 is concerned with the inequality of the society. It reads, “But it is manifestly opposed to natural law that a handful of people should gorge superfluities while the famished multitudes lack the necessities of life.”

Entry 192 is Religion and Socialism. It reads, “All idealistic considerations lead in the end to a kind of conception of divinity, and are, therefore, pure-non-sense in the eyes of the Marxists…The only scientific explanation of all the phenomena of the world is supplied by absolute materialism…There is no such thing as soul, and mind is nothing but a function of matter, organised in a particular way.”

Entry 276 is on Hindu civilisation. It is from the British journalist Valentine Chirol’s Indian Unrest. It reads: “It may seem to us to present in many of its aspects in almost unthinkable combination of spiritualistic idealism and of gross materialism, of asceticism and of sensuousness, of overweening arrogance when it identifies the human self with the universal self and merges man in the Divinity and the Divinity in man, and of demoralsing pessimism when it preaches that life itself is but a painful allusion and that the sovereign remedy and end of all evils is non-existence.” From the same source, his Entry 279 focuses on the constitution of free India.

Entry 287 presents total population of India (1921 census)–318, 942, 000 i. e. 1/5th of the whole human race. 2-1/2 million persons were literate in English–16 in every thousand males and 2 in every thousand females. Total number of vernaculars is 222. Total number of villages is 500,000.

His Entry on Arya Samaj is succinct. The Arya Samaj is a nationalist revival against Western influence. It pushes its followers in the Satyarth Prakash, the authoritative work of Dayananda, who was the founder of the sect, to go back to Vedas, and to seek the golden future in the imaginary golden past of the Aryas. The Satyarth Prakash also holds arguments against “non-Hindu” rule….

And his Entry 190 notes his thoughts on death: “If we were immortal we should all be miserable; no doubt it is hard to die, but it is sweet to think that we shall not live forever.” Who is telling? A man who is going to be hanged. A well-read man. He might have cried, as did Dr Faustus in his last hours. “O God! If thou wilt not have mercy on my soul, Yet for Christ’s sake whose blood hath ransom’d me, Impose some end to my incessant pain; Let Faustus live in hell a thousand years, A hundred thousand, and at last be sav’d! O, no end is limited to damned souls.” But he did not.

His Entry 29 on prison from Lord Byron’s “The Prisoner of Chillion” records his pain thus,

“There were no stars, no earth, no time,

No check, no change, no good, no crime,

But silence, and a stirless breath,

which neither was of life nor death.”

A man who knows the hour of his death is coming with the passage of each minute is reading the great poets, artists, thinkers, philosophers, historians, novelists, statisticians, theologians, orators, scientists, and statesmen, and he is taking notes from them. Does it not seem like to defy his punishment? Reading and writing can be pleasurable in prison if one is going to be freed. But one who is sure about the incoming death he is reading and taking notes from the great works of great thinkers is an act of martyrdom itself.

With his 33 Entry, I conclude. It quotes Charles Mackay’s poem, “No Enemies?” which helps us understand the martyr’s inner world.

You have no enemies, you say?

Alas! my friend, the boast is poor;

He who has mingled in the fray

Of duty, that the brave endure,

Must have made foes! If you have none,

Small is the work that you have done.

You’ve hit no traitor on the hip,

You’ve dashed no cup from perjured lip,

You’ve never turned the wrong to right,

You’ve been a coward in the fight.