By Peter Custers

On March 10, 1947, a day of non-cooperation was observed in the colonial province of Assam. That morning, Maulana Bhashani succeeded in evading the British intelligence services who had issued instructions to arrest him. He crossed the Brahmaputra river in a nauka, (a small boat), then travelled onwards by land in a bullock cart, eventually reaching the town hall of Tejpur. Here, thousands of peasants had gathered for a public meeting calling for the formation of a separate state of ‘Pakistan’, comprising Bengal and Assam. Though the day of action was sponsored by the Muslim League, claiming to represent exclusively Muslim interests, Bhashani’s speech was free of the communal rhetoric to which other Muslim League leaders were prone. He insisted that unity between Hindus and Muslims be maintained; his movement was directed against ‘British imperialism’ – not against any religious community.

Though Bhashani originally hailed from Sirajganj in East Bengal, (now Bangladesh), he derives his appellation ‘Bhashani’ from Char Bhashan, a low lying area of Assam. It was here, in the late 1920s, that Bhashani built his own hut, after having been forced by the British colonial authorities to seek refuge beyond the borders of Bengal. Before this shift, the fiery theologian had started distinguishing himself as an opponent of the feudal zamindari system which formed the backbone of Britain’s rule over Bengal.

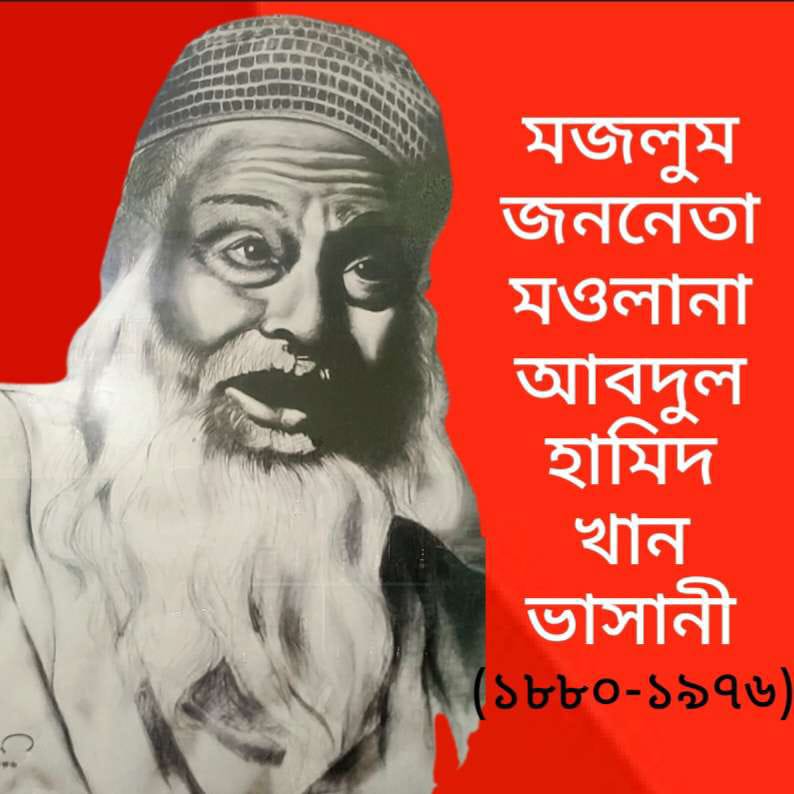

1920s Bengal saw the emergence of a movement for tenants’ rights protesting unjust impositions by absentee landlords. It was actively supported by rural intellectuals, including lawyers and Islamic preachers. Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan, later to be known as ‘Bhashani’, was a key organiser of this movement.

In Assam, the Maulana emerged as an effective and popular peasant leader, ready to champion the cause of the downtrodden. Perhaps paradoxically, he also emerged as a widely respected leader of the Muslim League and in 1944 he was elected the party’s President. The mass appeal which Bhashani developed via his support for immigrant peasants is illustrated by a short account of a Shammelan (conference) held in Mangaldoi, in 1946. The event is vividly described by the journalist-writer Abul Kalam Samsuddin, who had been invited to chair it. Arriving at the conference ground, Bhashani was greeted by a large crowd of peasants, raising their sticks above their heads. ‘There must’, Samsuddin writes, ‘have been at least two lakh, (200,000) participants!’ In a two-hour long speech to the conference, Bhashani criticised the British, but also singled out the police for atrocities committed against Bengali immigrants. Even his own Muslim League colleagues came in for criticism; Bashani exhorted them to work harder for the cause.

Just months before Mangaldoi, in April 1946, the Muslim League had won all but three seats in elections to Assam’s Legislative Assembly. This resounding victory, according to the biographer Syed Abul Maksud, should ‘almost entirely’ be credited to Bhashani. Yet, Bhashani was no conventional Muslim League politician. In 1944, at the very meeting where he was elected party President, Bhashani appealed to the League’s General Secretary, Sadullah, not to act as a ‘postbox’ for the British authorities. He was later to recall that, at a certain point during his stay in Assam, he had actually allied with the Congress party so as to press the Muslim League into action! Bhashani consistently used his standing as a religious leader and politician to advance the cause of the peasantry and on the eve of Partition, we find Bhashani combining the espousal of migrant peasants’ interests, with a principled opposition against communal hatred, and advocating the formation of a greater Bengal state.

Bhashani as religious leader

Writings eulogising Maulana Bhashani tend to focus on his politics, and the fact that he played a central role in the political evolution of (East) Bengal. This is a rather myopic view, for Bhashani’s politics cannot be understood without also taking into account the fact that he was a religious preacher with a huge following. Indeed, in Assam, Maulana Bhashani was widely regarded as a pir, a saint-like figure, commanding a large number of disciples who accepted his religious teachings, who were willing to support his politics, in particular his opposition to British colonialism.

Between 1907 and 1909, Bhashani attended the famous Islamic University of Deoband, where he received theological training. Deoband was widely regarded as a centre with progressive leanings. Several Sufi orders have influenced Deoband’s teachings. Its theologians are reputed to have shared an ‘anti-imperialist’orientation, and to have actively propagated the need to end Britain’s domination over the subcontinent.

There are clues to which current within Islam Bhashani ultimately chose to embrace in his essay on the policy of ‘Rabubiyat’, written in 1974, at the twilight of his political life. This essay indicates that, from 1946 onwards, the Rabubiyat remained his guiding ideology. The Rabubiyat preaches the undivided equality of all people, whatever their caste, nationality or religion. What makes Rabubiyat distinct is that it advocates the abolition of private ownership on the basis of faith. Bhashani states: ‘Man is only a custodian, whereas Allah holds ownership over all properties that exist. Thus, the state should abolish all private ownership, and should distribute things in equal proportions, on the basis of need’.

This statement reveals just how intertwined politics and religion were in Bhashani’s vision and life. Indeed, for him the message of Islam was so much a vision on how society should be structured economically, that he used every occasion to impress on his followers the need to engage in struggles for socio-economic change. Bhashani preached that the peasants needed to get organised.

Transition to secular politics

After Partition, Bhashani returned to East Bengal (East Pakistan). Here, he led a mass campaign in the 1950s in favour of regional autonomy and Bengali self-determination. This campaign was to play a key role in the Maulana’s journey towards the secularisation of politics, for the momentum which the movement for autonomy gained decisively demonstrated that the hold of the Muslim League and of Pakistan’s rulers over the minds of the population in East Bengal was weakening, and that secularisation was truly possible.

Bhashani had already protested in public against Pakistan’s economic exploitation of East Bengal in the late 1940s. Furthermore, he had also ensured that the demand stating that self-rule (swayatshashan) be granted to the province was included in the programme of the the (Muslim) Awami League, a new party formed as breakaway of the Muslim League in 1949. In the campaign for the 1954 elections he turned the demand for autonomy into the public’s ‘heartfelt issue’ (praner dabi), showing that electoral campaigning can contribute significantly towards a society’s politicisation.

After the party coalition he led had gained a convincing victory, he steadfastly continued building public opinion in support of self-determination, calling on students and other sections of the public to wear black badges on a province-wide day of resistance, and leading numerous rural demonstrations to vent the public’s discontent.

The 1957 Cultural Conference at Kagmari formed the culminating point of Bhashani’s campaign in favour of regional autonomy, and is considered to be a milestone in Bangladesh’s history. Bhashani, as the League’s President, called for a two day Council session of the party in Kagmari, Tangail, to be followed by a three day Cultural Conference. Bhashani used Kagmari to re-affirm the party’s ‘anti-imperialist’ stance. In his conference speech, Bhashani threatened – prophetically – that if East Bengal were not granted autonomy, the people would ultimately say ‘Assalamu Alaikum’ (goodbye) to Pakistan.

Even today there is a tendency amongst a section of Bangladeshi politicians, to obfuscate history and downgrade Bhashani’s achievements. It is critically important to underline how Bhashani’s campaign for regional autonomy, which reached its peak at the Kagmari Conference, both created the environment for the secularisation of politics, and formed the precursor to the 1971 war for the independence of Bangladesh.

Yet what nasty opposition the aged preacher-politician had to face! In the wake of the Kagmari Conference, conservative pirs and maulanas publicly vilified Bhashani, arguing that he was trying to disrupt Pakistan’s territorial integrity. Yet, despite all this, the history of East Bengal’s subsequent evolution attests that Maulana Bhashani was a political pioneer.

Bhashani’s struggle for secularisation of East Bengal’s politics started well before the Kagmari Conference took place. Thus, at a Council session of the Muslim Awami League in 1955, he proposed that the word ‘Muslim’ be dropped from the party’s name. And in his welcoming speech to the Kagmari Conference, he pushed aside Jinnah’s ‘two nations’ theory, insisting that, while it was a country with a Muslim majority, Pakistan was ‘for Hindus, Buddhists, Christians, adivasis and other small nationalities alike’. Bhashani stated that the communal problem was the ‘very biggest problem of the people of India and Pakistan’. He warned that if this problem was not resolved, the people of the two countries can never live in peace, and ‘all efforts at development’ will be utterly wasted.

The details registered above regarding East Bengal’s political evolution during the 1950s, reveal Bhashani’s key role in steering the transformation of East Bengal’s politics. Indeed, history attests that the 1950s saw a dramatic transition from the Muslim League with its communal grip over East Bengal’s politics, towards the secularisation of the region’s politics.

Maulana Bhashani did not just contribute to, but played the very determining role in achieving this historical transition. Via his leadership in the formation of East Bengal’s (Muslim) Awami League, via the consultations he held on abolishing the party’s communal bias, and via his speeches on the problematic relations between the Subcontinent’s main religions, Bhashani helped lay the foundations for the subsequent formation of Bangladesh as a secular state.

Bhashani’s class politics

Having highlighted Bhashani’s intense efforts to strengthen religious tolerance in East Bengal in the 1950s, it is now necessary to return to discuss the Maulana’s class politics. Here it should be stressed that, during the given historical period, Bhashani did not just stick to the policy he had pursued before, i.e. of championing peasant demands, but took it to a new stage. He invariably took a stance in favour of the demands put forward by various sections of the labouring population, such as industrial workers, fisher folk and peasants producing Bengal’s ‘golden’ fibre, jute. Moreover, Bhashani did not just use his leverage as a public opinion builder to promote these causes, he also took a personal interest in the self-organisation of each labouring class or section. The enhancement of class struggle was central to the methodology and strategy he used to defend religious tolerance.

Soon after his return to East Bengal from Assam, in the late 1940s, Bhashani agreed to champion the cause of waged workers employed in modern enterprises. Newspapers reports published in 1949/1950 record the sorrowful plight of workers recruited to labour for the province’s railways. Many lacked proper housing, and job security did not exist. Against this background, a union of railway workers was formed in 1949, and Bhashani was elected to be its President. In this capacity he is reported to have repeatedly spoken at gatherings of the union’s leading members, and he also participated in negotiations which the union held with the railway authorities. Four years later, the Maulana was again called upon to be president of another trade union. This time it was the union of workers employed in Adamjee Jute Mills, the largest industrial complex in East Bengal at that time.

One personal initiative which the Maulana undertook was regarding the formation of East Bengal’s union of fisher folk. This initiative dates from 1958 and was launched immediately after Bhashani had parted ways with the Awami League, and had formed his own Leftist party, the NAP. (National Awami Party). NAP’s programmatic documents expressed unequivocally Bhashani’s combined orientation, on class struggle from below and on religious tolerance. The document also referred to the need for ‘land reform’. In 1958, he launched a month-long drive to help prepare for the holding of a conference of fisher folk. Over a hundred delegates are reported to have gathered for this event, termed ‘singular’ in the history of Bengal.

The Shammelan adopted a 12-point charter of demands, with strikingly concrete propositions, including: that import licenses for fishing gear be offered to professional fishermen, that floating hospitals be set up in fishing zones, and that anyone owning a net should be granted rights over water bodies. Again, not long before he had started his drive in support of fisher folk, in January 1958, the Maulana had already taken the initiative towards the formation of a peasant association, the East Pakistan ‘Krishok Samity’. Soon after, however, the process of organising in the rural areas was disrupted, when the military took over state power and imposed Martial Law.

It was only in 1964 that organising could be re-intensified. Clearly, the aged Bhashani in the Pakistan period made sustained efforts to promote the formation of union-type organisations, both in villages and towns of East Bengal. By the end of the 1960s, these efforts bore fruit and in a very explosive manner. Unfortunately, in this brief essay, there is no scope to give a detailed description of Bhashani’s role in the 1968/69 uprising against military dictatorship. It should be noted, however, that he personally launched an uprising in East Bengal, via a general strike held in Dhaka on December 7, 1968, and that he personally helped shape other tactics employed by the rising’s participants. In the aftermath of Ayub Khan’s fall, Bhashani’s leadership in the uprising drew much international attention.

In the late 1940s, just after Partition, the sphere of politics in the province had largely been communalised. By the late 1960s, through the intense and sustained efforts which the Maulana and other politicians opposed to intolerance had made, the impact of communal parties in East Bengal had dramatically declined. The change in public discourse was very visible in the uprising against Ayub Khan’s dictatorship. The very success of this uprising indicates that the state could no longer exploit religion to manipulate the sentiments of East Bengal’s population. Politics had largely been secularised.

Conclusion

Bhashani’s efforts should be assessed within a broader, longer- term perspective on religious tolerance and the history of Bangladesh. Here two points may be re-visited: First, Bhashani did not try to position himself beyond the parameters of a single religion. Bhashani’s way of identifying with Islam, it may be argued, limited his scope for incorporating syncretic elements derived from other faiths into his own world view. While he surely displayed an affinity with Bengal’s syncretic tradition, his approach was different from, for instance, the poet-writer Nazrul Islam, who used an imagery derived from both Hinduism and Islam. Nevertheless, Bhashani’s championing of religious tolerance from within the framework of Islam has its own, positive, importance for the contemporary debate on religious tolerance. For at a time when right-wing, Western politicians are trying to make their public believe that there is an irreconcilable conflict between the values of religious tolerance and the nature of Islam, the example of Maulana Bhashani reveals, with full force, that the opposite is the case.

Peter Custers (1949-2015) was a Dutch journalist and researcher who worked extensively on South Asia, particularly Bangladesh.

This is a summary of an article published in the The Indian Economic and Social History Review (IESHR) April-June 2010 issue, Vol.XLVII no.2, p.231: Peter Custers, ‘Maulana Bhashani and the Transition to Secular Politics in East Bengal’.

(This article was published in The Daily Star)