Introduction

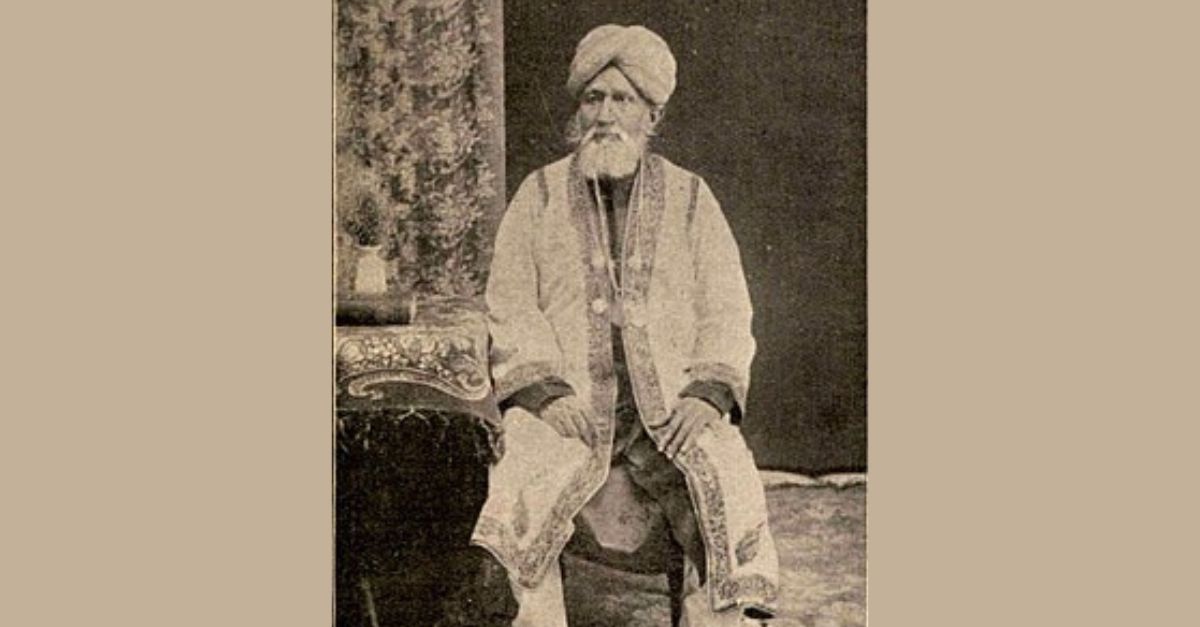

Of the most important figures of the ‘Delhi renaissance’ was Mohammad Zakaullah. He is often called Munshi Zakaullah or Maulvi Zakaullah. Zakaullah was born on 20 April 1832. From his student days, he enjoyed reading and writing.

Zakaullah started writing at the age of nineteen, and published thousands of pages. Literature, history, and science were genuine passions of his. He served as a teacher at Delhi College, Agra College, as headmaster at the Delhi Normal School, as deputy inspector of schools in Bulandshahar and Moradabad, and as professor at Allahabad’s Muir Central College.

Some of Delhi’s leading lights were in his circle of friends: Nazir Ahmad, Hali, Muhammad Husain Azad, Maulvi Karim Bakhsh, Piyare Lal Ashob, Kanhaya Lal, Mir Babar Ali, Master Nand Kishore, and Maulvi Ziauddin.

Intellectual life

Zakaullah looked at the future with hope, not with despair. He welcomed the new education the British offered, and privileged the advance in science over previous accomplishments. His vision included a reformed educational system, be it primary, secondary or higher, that would realise universal education in the vernaculars for boys and girls. His influence extended well beyond Delhi. Maulvi Imdad Ali, founder of the Bihar Scientific Society and editor of Akhbarul Akhyar, was one of his allies. So was Delhi’s essayist-journalist, Mir Nasir Ali.

Another strong partner was Abul Kalam Azad, who launched the Lisan-ul Sidq in 1902. His translations were prescribed in schools. Yet the verdict of history went against Zakaullah. In 1900, Aligarh College, along with other institutions, began teaching English up to the M.A. level. Urdu ceased to be either the principal source of scientific information, or even the language of middle-class professions like law and medicine. Zakaullah would say how his life’s work of Urdu adaptation and translation had been wasted.

Experiencing 1857

Zakaullah was shattered experiencing the revolt of 1857 and spoke about those weeks and months, of torture and hunger, of dread and horror. The current of life that had run so smoothly during his childhood changed into a whirling torrent in the days of the Mutiny. Bahadur Shah’s unceremonious fall was a great psychological blow. To a family steeped in learning and scholarship, the loss of libraries brought pain. His house near Red Fort was demolished, the family’s property was confiscated, and they had to take refuge.

However, we do not find Zakaullah shedding tears at the loss of Muslim political sovereignty; he grieved over the loss of close and intimate friends. He never accepted the logic of either the mutineers or the British. He preferred peace, and stability. Quickly, he started rebuilding his nest anew. He wanted the educated Muslims to look at the future without being entangled by the cobweb of the past accomplishments.

Zakaullah, the historian

It was Zakaullah who introduced the methods of secular study in Urdu historiography. He wanted historians to record objectively and empirically the society’s high and low points, without subordinating the study to political expediency. The true purpose of unravelling the past is to make its study relevant to the future generations. He admired historical figures like Asoka and Akbar as they practiced religious tolerance. Zakaullah wrote two biographies, one on Queen Victoria and the other on Curzon. He salutes the era of peace and administrative innovations benefiting the people like the railway system and the irrigation projects ushered in by the British sovereign.

Zakaullah, the mathematician

When he was nineteen, Zakaullah produced Tuhfatul Hisab, an excursion into modern mathematics. It was Ramchander who sowed in Zakaullah’s mind and heart a love for mathematics. In the 1870s, Zakaullah brought out a series of twenty-three volumes in Urdu which were published under the aegis of Aligarh’s Scientific Society and Bihar’s Scientific Society. Four of the volumes were translations of Euclid (about 300 BC), the Greek geometer. Elements (thirteen books), his chief work, formed the basis of later works in geometry.

Zakaullah produced four treatises on plane and one on spherical trigonometry. He translated the English mathematician, Isaac Todhunter’s work on the differential and integral calculus, and the school manuals by Galbraith and Haughton of Queen’s College, Ireland. The translation of so many works was a monumental feat, and a welcome support to the argument for teaching science in the vernacular.

Views on communal harmony

In Zakaullah’s writings, the ideas of nation, and national belonging are paramount. He discussed this hubul watani: “India is our mother country, the country that gives us birth. We have made our homes here, married here, begotten children here; and here on this soil of India, which is mingled with the dust of our ancestors. For a thousand years, our own religion of Islam has been intimately bound up with India.”

Inter-community relations during Zakaullah’s lifetime were mostly cordial. He believed that in a country of diverse faiths, government should not extend preferential treatment to a particular community. He avoided theological controversies and made cultural pluralism an article of faith. Zakaullah insisted upon the importance of inter-faith dialogue which ought to be conducted with grace, and civility. He admired some aspects of Christianity and Jesus Christ’s message too.

Lived Islam and religious pluralism

Zakaullah found Islamic ideals to be refreshing. He cherished them, invoked them, and furthered them in his writings. Honesty, truthfulness, loyalty to friends, and concern for the needy are not exclusive to any particular religion but are found in all great civilizations. Zakaullah looked upon the Islamic ethical ideal broadly akin to the ethical ideal of other faiths. Islam, he felt, as a faith is fully compatible with science.

Indeed, the Islamic system was immensely richer and intellectually more sophisticated than that of Europe in the Middle Ages. It involved engagement with other communities, thus paving the way for spiritual diversity. In this way, he transcended religious parochialism and graduated to a larger concept of religious pluralism. Islam, for him, provided considerable freedom to retain regional, linguistic, and class identities.

Death and legacy

His outward manners, dress, habits, and religious life were an intrinsic part of Delhi’s ethos. Reading him is to understand the society and culture of the nineteenth century Delhi. His works deserve wider recognition. As a core contributor to the ‘Delhi renaissance’, he is mostly forgotten by even progressive historians. Follower of the Chishti path, Zakaullah was buried at the shrine of Sufi saint Shah Abdul Salam Faridi after his death on 7 November 1910.

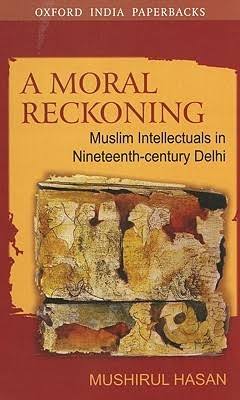

- This short essay is based on Mushirul Hasan’s book A Moral Reckoning: Muslim Intellectuals in Nineteenth-century Delhi (2005, OUP).