“Tajuddin, I wish to bow to you, but I cannot as you are much younger than me. In the field of historical study of Murshidabad you are the last name (invincible authority). Our country, our people will remember you.”

—-Soumendra Kumar Gupta, author of Murshidabad Itibrita: Vol-I & II

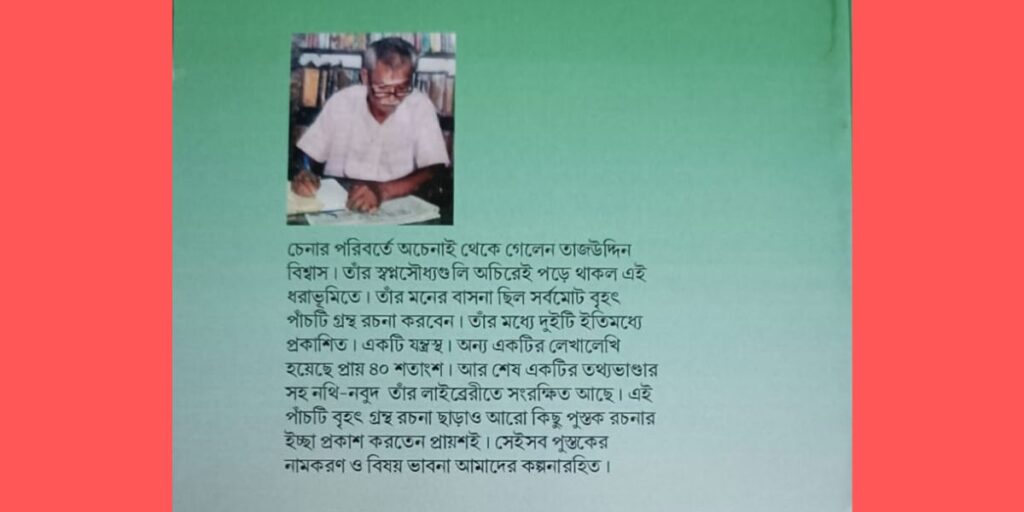

I would not write a single sentence unless Tajuddin Biswas (1946—2021) were a good man. He was a man with a mission. Each step on earth was marked by his hard work, reliability, sincerity, honesty, and frankness. He worked as if he was driven by some inner urges. Not hankering after name or fame, his dedication to his work, and his obligation to his soil made him great. He left a rich historical legacy to the posterity. He was a haloed path to scholars across continents in general and especially to Bangla-speaking history scholars of West Bengal. People should be familiar with the man and his work.

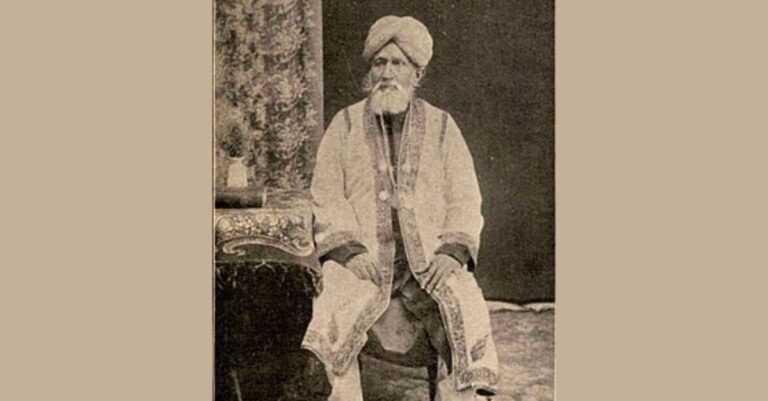

Yes, he is a rural historian of the district Murshidabad, but, as noted historian Akshay Kumar Maitreya put it, to write regional history is the obligation of a genuine historian; regional history is the bedrock of world history.

Tajuddin Biswas was a versatile man we buried at Romna Eitbar Nagar burial ground, Dumkol, on 3rd April 2021.

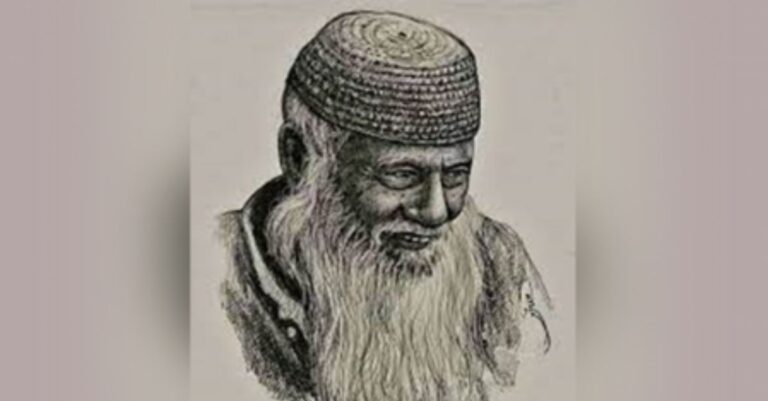

Tajuddin Biswas was born on May 13, 1946, to a peasant family at Fatehpur village under Dumkol police station in Murshidabad. His father was Samiruddin Biswas, and his mother was Aklima Khatun. His grandfather, Raisuddin Biswas, popularly known as ‘pandit’ as he knew Sanskrit, Bangla and Parsi, was a famous name in the history of the 1924 Murshidabad Indigo movement. It started from Fathepur village, 46 Vaghirathpur Mouza, under Dumkol police station under the leadership of Raisuddin Pandit and his two active followers, Sabir Ali Mondal and Abdul Bari Biswas.

Tajuddin Biswas was a son of the soil. He was a genius. He was a poet, storyteller, novelist, essayist, scholar, historian, and authority on land survey, deeds, records, maps, coins, etc. He was a human rights activist and a Naxalite. He was the president of Purba Bharat Bangla Sahitya o Sanskriti Parishad. He was an active member of Nazrul Academy for Humanity, Nadia Loksanskriti Parishad. He also co-edited a local journal, Murshidabad Arshi.

During 1988 Murshidabad Katra Masjid Massacre, he founded a Hindu—Muslim Samannoy Mancha at Dumkol to douse the flame of communalism, as his long-time friend Kartik Das recalled. He was deeply influenced by the ideals of great orator cum talented politician Syed Badruddaja (1900-1974), revolutionary poet Kazi Nazrul Islam and a Naxal leader of Murshidabad, Anantya Bhattacharjee.

He had a checkered life. Despite extreme poverty in the family, he got degrees and diplomas from various higher education institutions such as Berhampore K N College, Bhagalpur University, Jadavpur University and Hyderabad University.

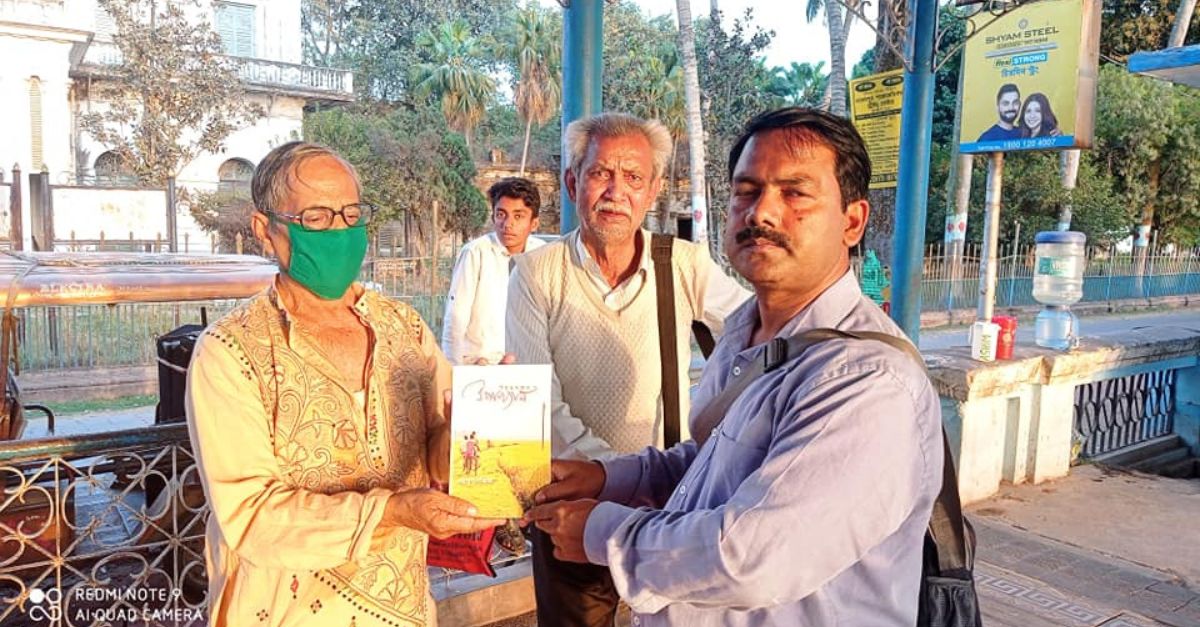

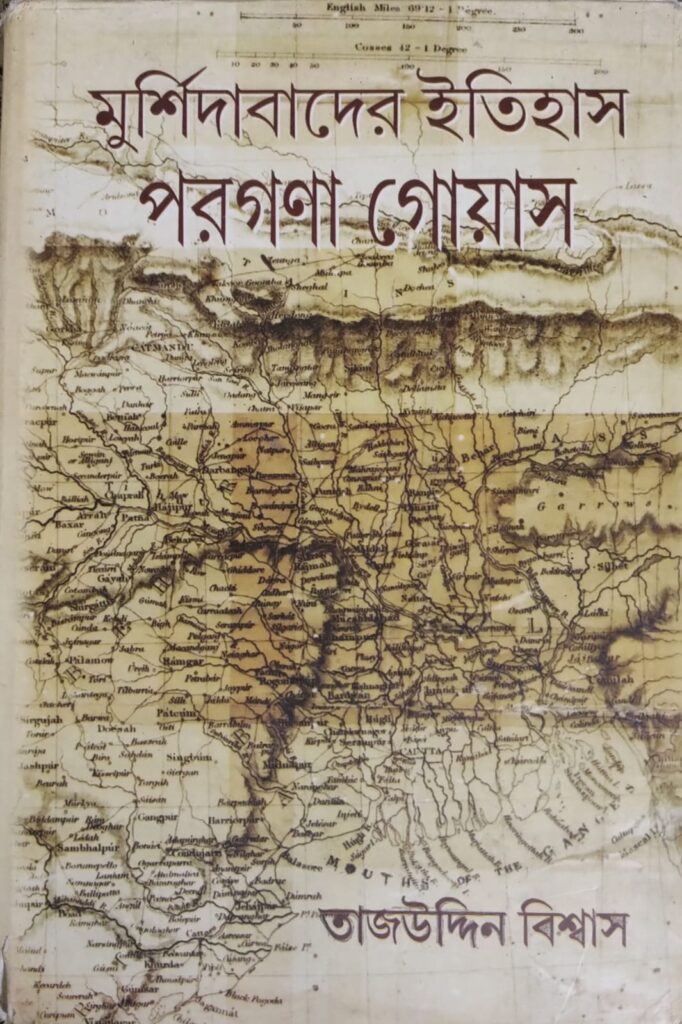

His two major works, Murshidabder Eithihas: Pargana Goas (2016) and Murshidabader Eithihas: Gram o Goron (2018) have already earned acclaim and accolades from researchers in Bangladesh and America. These works are the direct result of his forty years of field research. Not a single village exists in Murshidabad where his footprints cannot be found. Such a dedicated, tireless, honest scholar he was.

His 660-page Pargana Goas is a testimony to his historical leanings. It minutely records the history of Goas, a locality between Berhampore and Sagarpara High Road, 3 km away from Islampur. In 1582, during land reforms initiated by Todormol, Goas was first recognised as a pargana. However, it was a wealthy locality crucial for its connectivity through canals, rivers, and streets. It was mainly a commercial centre. Dumkol, Azimgaj, and Beldanga haats were famous for betel leaves and cotton materials. Doulatabad haat was also famous for betel leaves. Out of cotton materials, weavers used to make sari, lungi, gamacha, etc. and made, thus, a living. They mainly lived in villages –Harurpara, Raipur, Jalangi, Nabipur, Sagarpara, Nowdapara, Dhanirampur. Paragana Goas is a testimony of the living legacy of Goas and includes data, land maps, land records, photos of masjids, mandirs, and ancient trees. Today’s Goas is not the same. The book has also encapsulated its gradual changes in terms of its shapes, sizes, textures and structures.

His 800-page book, Murshidabader Eithihas: Gram o Garan is basically an analytical look through the history on the composition of the villages of Murshidabad. As the title suggests, it records the history of 2289 villages in the district of Murshidabad. It minutely details their individualistic structure, causes of formation, the origin of their name, area, boundary, population, livelihood, mandir, masjid, canals, ponds, water bodies, waterways, trees, food habits, culture, festivals, administration, etc. It is a living history sincerely penned by a man who, from dawn to dusk, trots tirelessly in and around the villages of Murshidabad on almost all the days of the year.

His other noted books to be published include Murshidabader Eithihas: Gram o Manush, Murshidabader Eithihas: baekti o Baektitto, Murshidabader Eithihas: Gram o Sanskriti, Murshidabader Eithihas: Jol o Jangal, etc.

As the chronicler of fictional Yoknapatawpha, Southern American writer William Faulkner (1897-1962) emphatically put in his fiction Requiem for a Nun (1938), ‘The past is never dead. It’s not even past.’ The same can be said about the chronicler of the villages of Murshidabad, Tajuddin Biswas. In many ways, he is one of the pioneers of living rural history of Murshidabad.

He was awarded Dr Ambedkar Fellowship (2019) by the Bharatiya Dalit Sahitya Academy for his book Gram o Garan.

We pay homage to this learned, humble son of Murshidabadi soil.