Introduction

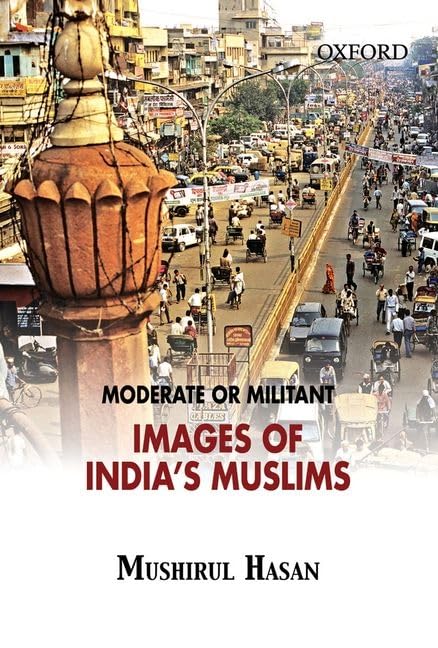

The book at hand is by Mushirul Hasan. I know of his two major interventions in the world of academic history. First, is his research on nationalist Muslims and their support for a multi-religious society for an undivided India. Second, is his work on the history of Muslims in the Indian sub-continent. It was his edited volume Inventing Boundaries (2000), where I first noticed his deep empathy for the plight of women. The volume had essays from Ritu Menon, Kamla Bhasin, and Urvashi Butalia.

The book that I am reviewing talks about the myth of militancy among Muslims and shows the true picture of moderation. He is concerned, both as a Muslim and as a historian, about the rising prejudice against Muslims in India. This isn’t comforting because India has a long history of Muslims living side by side amicably with their non-Muslim neighbours. This book is a response to this growth of ignorance and antipathy towards Muslims and their religion- Islam. My review consists of two major sections: first, I talk about some of the key arguments made in the book and second, I speak on how two Muslim women described their experience of the partition of India.

Key Arguments

Mushirul Hasan takes upon himself the task of writing the story of Muslims in India

sensitively. He quotes Leopold von Ranke (1795–1886): ‘The writing of history is a matter of conscience’. It should be taken as a serious intellectual intervention that can have political ramifications. A historian should not allow populist sentiments to rule over his ethical responsibility to serve society at large. Alfred Cobban (1901-68) said that any interpretation in the field of history must stand or fall by its consistency with evidence.

We see Hasan to be committed to Nehru’s idea of nationalism and Tagore’s idea of internationalism. Hasan quotes from Nehru’s Glimpses of World History: ‘So, while kings quarrelled and destroyed each other, silent forces in India worked ceaselessly for a synthesis, in order that the people of India might live harmoniously together and devote their energies jointly to progress and betterment.’ Similarly, Hasan says that scholars from Jamia Millia Islamia like Mohammad Mujeeb and Abid Husain were staunch supporters of Mahatma Gandhi. In Gandhi and Communal Unity, Abid Husain interpreted, ‘if we loved our country, the human race and the pursuit of Truth, we had to dream with Tagore and realize our dream in action with Gandhiji—to see Truth with Tagore and live it with Gandhiji’.

Pluralism has been the hallmark of India’s long history, no doubt. Rishi tradition in Kashmir, Imamshahi tradition in Gujarat and Sufi shrines all over the Indian sub-continent are living examples of this pluralism. Writing about Delhi, CF Andrews said, “The intimate residence together side by side in the same city of Musalmans and Hindus had brought about a noticeable amalgamation of customs and usages among the common people.”

It is clear from the book that communalism was created by the British to divide and rule India. This was created through the Orientalist image of Muslims being spread globally since early modern times. Sadly, many Hindu writers and publicists bought these stereotypes against Muslims. This exacerbated the anti-Muslim sentiment and communalism took root in the 1930s. The new form of administrative language overemphasised one’s religious identity over all other parameters. This threatened certain quarters that were against the Poona Pact in 1932. This line of thought was well-developed by Br Ambedkar in his Communal Deadlock and a Way to Solve It (1945). The construction of Muslim identity in the colonial context has been studied by some scholars. For Hasan, it was a complex process. He asks his readers to read the autobiography of Mohamed Ali’s My Life: A Fragment to understand the nuances of the influence of colonial administration on the identities of all Indians, including Muslims.

Women’s Voices During the Partition

Mushirul Hasan has used not only archival material but also fiction to comprehend the

complexity of Partition. He quotes Manto and Ismat Chugtai to tell his readers how it was

living in those turbulent times. The book tells us that it is the women who bore the brunt of

violence, relocation, and uprooting in more than one way. In her heart-rending poem ‘Aaj

Akhan Waris Sah Nun’ (I say unto Waris Shah), Amrita Pritam (1919–2006) wrote that ‘the

Chenab has turned crimson’. Hasan has not portrayed women as victims of violence and

abductions but as survivors and narrators of their own stories. Two examples deserve

attention.

Sunlight on a Broken Column is a novel by the Lucknow-born Attia Hosain (1913–98). Attia

Hosain came from a taluqdari family of Awadh and studied at La Martiniere School for Girls

and the Isabela Thoburn College in Lucknow. She was the first woman graduate from any

taluqdari family. She took part in left-wing activities and attended the first Progressive

Writers’ Conference and the All-India Women’s Conference in Calcutta in 1933. Her novel is set in this cultural and social milieu. Sunlight on a Broken Column is mostly about a feudal

society trying to come to terms with the uncertainties of Partition and the forthcoming

political set-up. She left for London in 1947, lived there home-sick, and died far away from

her motherland. One can see in her work how much she cherished liberal values and

Lucknow’s composite culture. It is here that her humanistic worldview was germinated.

Partition left her shattered.

The Heart Divided is a quasi-autobiographical novel by Mumtaz Shah Nawaz (1912–48)

based on Punjab. It focuses on the years 1930 to 1942 and traces the idea of a separate

homeland for the Muslims through the lives of two sisters, Zohra, a Congress supporter, and Sughra Jamaluddin, a League worker. Mumtaz Shah Nawaz was extremely active in her own personal-political life. She wrote letters to Nehru, penned socialist poetry, and participated in Congress sessions. She was disillusioned with the Quit India movement and organised Muslim women under the aegis of League. Reading this work of fiction one is left wondering why Muslims were getting alienated from the Congress from the late 1930s. “[W]hy did the Congress baulk at separate electorates, calling them anti-national and narrow- minded? Why did it do nothing to allay the Muslim fear that the freedom the Congress promised meant freedom for … all? Seen from the Muslim point of view, ‘nationalism’ increasingly began to mean thinking and living in the ‘Hindu Congress’ way… Those living or thinking another way became anti-Indian,” laments Hasan.

Conclusion

On reading the book I realised that Mushirul Hasan was a die-hard optimist who would never bend to the dark and gloomy prophesies. I find many scholars and columnists to be passively accepting that Islamophobia is growing to increase in the coming decades. Reading them one is filled with negativity and pessimism. Hence, I felt to review this book so that Muslims can conceive of a bright future. The two women, whom I mentioned in the review, are not portrayed as victims but as strugglers against the vagaries of time. They are the narrators of their story; a story where they have participated actively for a secure future.

In this book, I sensed a vision for the future of the Muslims in India that Mushirul Hasan must have dreamt of. He wanted Muslims to be a securer of justice not only for Muslims but also for the non-Muslims of the world. This is a message for global peace and communal harmony.