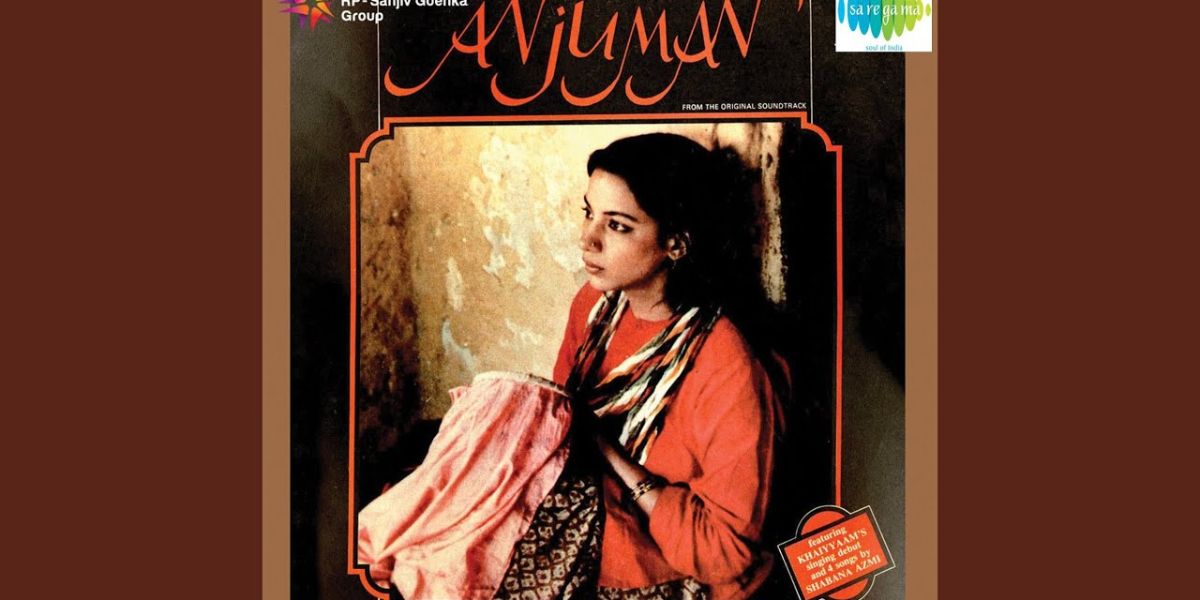

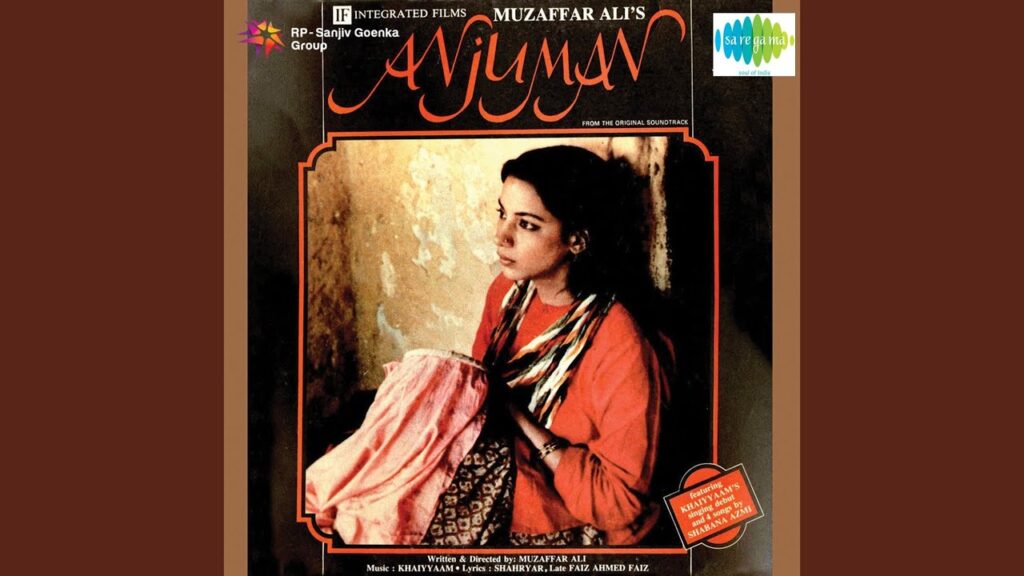

Anjuman

Directed by Muzaffar Ali

Produced by Muzaffar Ali & Shobha Doctor.

Duration: 2hr 20 mins

Dil na ummeed to nahi, na kaam hi to hai.

Lambi hai gham ki shaam magar, shaam hi to hai.

-Faiz Ahmed Faiz

Anjuman (1986) captures the fleeting moments of old and decaying Awadh and its eroding culture. Like his other films Gaman (1978) and Aagaman (1982), Muzaffar Ali has used the lens of economic inequality, crippling human existence. It is the predicament of the disposed that drives Ali to make films and portray the human condition sensitively and movingly. Set against the backdrop of old Lucknow, the film takes us through the city’s narrow lanes and derelict walls. Here, women wear burqa and gharara, and men don sherwani and broad pajamas. It is a poignant exploration of a struggle against economic inequality, where women are not victims but the agents of change. It is a poetic ode of persistent hope against abiding despair. It is sheer magic on celluloid.

A woman of determination, struggle and hope

Anjuman, played by Shabana Azmi, is the protagonist of the film. Her father has deserted her mother, Gulshan Ara. Now, Anjuman is staying at her maternal uncle’s place with her younger sister and younger brother. Maternal uncle Jahaandaar Mirza is genial and takes care of his elder sister (Jahaan Ara) and her three children despite being a man of modest means. His wife (Raunaq Jahan) is an irritable woman who detests the presence of Anjuman and her family. She finds them an economic burden and constantly asks her husband to kick out Anjuman and her family. This familial tension naturally takes a toll on Anjuman’s mental well-being. Her mother squabbles regularly, mainly due to financial constraints and societal pressure. Despite all this, Anjuman makes time for herself: time to read and write Urdu poetry and delve deep into existential questions. Her adverse circumstances do not embitter her; she is resilient and hopeful. Main raah kab se nayi zindagi ki takti hoon (by Shahryar).

Sectarianism: A plot against economic and gender justice

This is not the only challenge that Anjuman faces in her life. This is just one among the many. She, along with her mother, works as a chikan-kaar. Chikan is a unique style of embroidery developed generations ago in the erstwhile Awadh region. Despite the duo working from dawn to dusk, they struggle to make their two ends meet. Mamujan (Jahandar Mirza) is their last resort. This is also the story of almost all the women embroiderers. This poverty is caused by the traders who sell the final product in the regional and national markets and make huge profits. These traders live lavish lives; they stay in opulent mansions (havelis), have leisure time to play chess and smoke hookah, and hold hostile prejudices against socialism (read economic equality) and women chikan-kaars (read gender equality). Anjuman finds herself in a tough fight against the traders and their henchmen. She understands that the Shia-Sunni conflict in Lucknow is the plot of the rich against the poor so that the poor can never demand just wages. Both sects live together organically, just like Hindus and Muslims. Rich people pit one group of poor against another so that they can keep on maintaining class hierarchy.

Comradeship across class

We find Anjuman struggling not only in her professional life but also in her private life. She is fond of a man who is her neighbour and of royal descent. Raja Sajid, played by Farooq Shaikh, is a man of genteel character and poetic sensibilities. He lives in the Tijwara estate palace with his mother, Rani sarkar. He is rich, connects with the Indian elite, and speaks English fluently. Yet, he is grounded and finds himself habituated to the ethos of purana Lucknow. They have a vintage car which is slow, and a languid lifestyle. Sajid is both classic and classy. Anjuman and Sajid get along well and even dream of marrying each other. Raja sahab, as he is often called, has an empathetic disposition towards the struggles of the chikan workers and even supports their cause secretly. But the class difference is too much for him to bridge. Later, Anjuman accepts her dejection as a working-class woman. ‘tujhse hoti bhi to kya hoti shikayat mujhko.’ Sajid transforms from lover to comrade. We find Sajid following Anjuman in her march against oppression and tyranny.

Women as change-makers

Anjuman, both the film and the character, is not exclusively about the protagonist. It is equally about the firmness and courage shown by fellow embroiderers as a collective (Anjuman means congregation in Urdu). They all work hard to sustain their families and support Anjuman when she goes on to form a workers’ union to demand a fair share from rich and corrupt traders and business people. Even when the traders use local goons to attack them physically and issue threats to stop demanding fair wages, those innumerable women refuse to budge. Hundreds of burqa-clad women join Anjuman and raise slogans against injustices and inequality. They find a new consciousness after meeting an eye specialist, Suchitra Sharma, played by Rohini Hattangadi. Dr. Sharma is a staunch supporter of economic justice and gender equality. The film revolves around female characters, where Shabana Azmi keeps the audience enthralled with her acting (and singing) skills. Yes, this is a film in which she even sang her songs. There is also the character of Naubahar bua, a transgender person serving at the kothi (palace) of Rani Sarkar, where she enjoys being a trusted employee. She is considered part of the family by the Chikankar women.

Aesthetics of old Lucknow

Each frame of Anjuman is infused with lyrical beauty and melancholic grace of the purana Lucknow. One gets to rejoice the aesthetics of the Awadh culture through its meticulously crafted depiction of quotidian life. The three giant domes of Bara Imambara appear in silhouette against the sky lit by sunset. People recite Urdu couplets at every nook and corner of the Lucknow city. Quirky characters like Chuhiya Begum, played by Shaukat Azmi, and Banke Nawab, played by Mushtaq Khan, lighten the viewer’s heart with their comic gestures. We find the royal mannerisms in the gait of Raja Sajid and his mother, who could speak only in Awadhi. Young boys fly kites while young girls cover their heads with rupatta. Anjuman (1986) paints the finely woven cultural fabric of Awadh: adaab and tasleem are heard everywhere, paan-daan is seen everywhere, and paratha-chai is relished everywhere. The film has the aroma of khutiya, a local Lakhnawi sweet bought from the Naqqas market.

Contemporary relevance

Finally, the poetic, rich texture of the film deserves special mention. Faiz Ahmed Faiz is rendered eternal via the song, kab haath me tera haath nahi, kab saath me tera saath nahi, and several couplets recited by Anjuman across the film. Music by Khayyam and dialogues by Rahi Masoom Raza make Anjuman (1986) a timeless piece of art and a milestone in the history of Indian cinematic expression.

(jointly written by Zeeshan Husain & Qayam Masumi)